A team of marine biologists and First Nations are working around the clock to save an orphaned orca calf after its mother died last week on the northwest coast of Vancouver Island.

Kʷiisaḥiʔis (Brave Little Hunter), named by the local Ehattesaht First Nation, has been trapped in the Zeballos lagoon where its pregnant mother became stranded in low tide and later drowned on March 23rd.

Jared Towers, Executive Director of Bay Cetology, is part of the marine mammal rescue team and has offered his organization’s artificial intelligence technology to track and reunite the calf with nearby relatives.

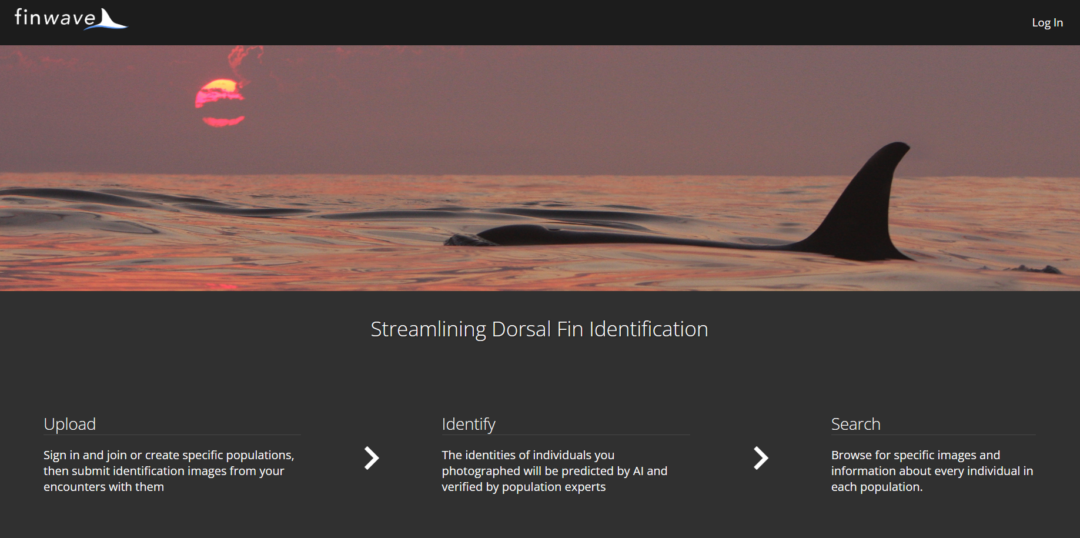

Bay Cetology created an innovative online photo-identification database called Finwave that recognizes individual Bigg’s killer whales using their dorsal fins and other distinguishing marks. Users can upload their photos into the database and artificial intelligence will identify the whale so researchers can precisely track their movements.

“Deep learning algorithms have been built to take any photo and automatically detect whether or not there is a killer whale in the photo and if there is, tell us exactly who that individual is,” Towers explained.

Earlier this week, Bay Cetology posted on Facebook that they would be making the AI technology available to anyone who wanted to upload photos to help locate Brave Little Hunter’s family. “Within an hour of making that post on Facebook, we knew exactly where the family was,” he said.

“Using photo identification to track killer whales is not new,” Towers added. “It’s something that has been going on for over 50 years – we started with film and moved into digital in the mid-2000s, and right now, we’re on the brink of moving into AI.” The database currently has 250 contributors, including participants from Fisheries and Oceans Canada, North Island Marine Mammal Stewardship Association, Ocean Wise, and whale watching tours.

Rescue Efforts Continue

Tower’s organization has been closely monitoring the calf’s health and behaviour alongside a large rescue team composed of other whale experts, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and First Nations to try to aid the young mammal in navigating out of the lagoon.

The orca calf’s exit from the lagoon is contingent on the tides, which are currently too low, and its ability to hurdle a sandbar, which is preventing it from connecting to the open ocean. “It’s not only a matter of depth, it’s a matter of timing, and it’s a matter of physical obstruction,” Towers said.

Time is of the essence, as experts are worried the two-year-old calf may have been relying on its mother for milk and food, and may starve if it goes two weeks without any sustenance. Though Brave Little Hunter, a carnivorous Bigg’s killer whale, was photographed with a bird in its mouth a few days ago, DFO is now taking feeding measures like placing harbour seal remains in the water.

Rescuers have also tried various methods to assist the calf in making it over the sandbar, including playing whale call recordings, immersing metal pipes in the water to form a ‘sound wall,’ and Indigenous drumming. Towers says the rescue team is now considering a capture-and-release method to lift Brave Little Hunter past the sandbar.

“In many ways, it feels as though by coming together for Kʷiisaḥiʔis, we are beginning to mourn and heal with this youngster.”

Jared Towers, Executive Director of Bay Cetology

“There are some plans in place that we are moving forward with next week, but they’re really contingent on the animal’s health and cooperation, and that involves just being ready to respond on a whole different scale,” he said.

If captured, the animal would then be placed in the open ocean to reunite with its relatives who were last spotted in Barkley Sound off Ucluelet – about 150 nautical miles south of the lagoon where the orca calf is currently located.

Yet Towers thinks that there may be another reason the whale won’t leave the lagoon – grief. “Basically, this little one is telling us it’s not ready to go at this time, and there’s nothing we can do but respect that. The general consensus in the community and among those of us on site is that Kʷiisaḥiʔis is mourning,” he wrote in a Facebook post. “In many ways, it feels as though by coming together for Kʷiisaḥiʔis, we are beginning to mourn and heal with this youngster.”

Iconic Orcas

Towers highlighted that this rescue effort has been made possible through close collaboration with the Ehattesaht First Nation. “Having the opportunity to work together with them on this has been such a beautiful experience, I think, for everybody involved,” he said. “There’s been a lot of good teamwork, a lot of mutual respect and gratitude, and a lot of ideas – and there’s space for all of them at the table, and that’s really important because it is a very unique situation.”

“If we don’t give our best efforts and come together to save Kʷiisaḥiʔis, then I think it really casts a poor light on us as a species, given what we know about these animals and how important they are to so many people around the world.”

Jared Towers, Executive Director of Bay Cetology

“The community is really affected by it spiritually,” Ehattesahtt First Nation Chief Simon John told CBC News, explaining how hard it has been to see the calf struggling. “All we can have is hope,” he said.

When Towers was asked why he thinks this young orca’s story has captured the public’s attention and hearts, he was quick to point out how significant these marine mammals are to West Coasters.

“Killer whales are iconic in our culture, but they’ve also been iconic in First Nations cultures for generations,” he said. “If we don’t give our best efforts and come together to save Kʷiisaḥiʔis, then I think it really casts a poor light on us as a species, given what we know about these animals and how important they are to so many people around the world.”

“We really have a responsibility to do our best to save this little one,” he added.

Published with the permission of The Skeena.