Among the most captivating residents of BC’s coast are the nudibranchs, commonly known as sea slugs. These shell-less molluscs are known for their vibrant colours and adorable appearance. One particularly fascinating species gracing BC’s waters is Cockerell’s nudibranch, Limacia cockerelli. This small but ecologically significant creature offers a window into the intricate web of life thriving beneath the waves and underscores the importance of protecting these fragile marine ecosystems.

A Splash of Colour: Identifying Cockerell’s Nudibranch

First described by Frank Mace MacFarland in 1905 and named in honour of the prolific naturalist Theodore D. A. Cockerell, this nudibranch is a striking sight for divers and intertidal explorers.

Typically only reaching lengths of up to 2.6 centimetres (about an inch), Cockerell’s nudibranch boasts a distinctive appearance. Its body is generally translucent white or cream-coloured. What truly sets it apart are the numerous club-shaped dorsal papillae, which are longer around the margins and shorter towards the centre of the back. In the northern variant, found along the BC coast, these papillae are often tipped with a vibrant orange or reddish-orange, contrasting beautifully with their white bases.

Like other dorid nudibranchs, Cockerell’s Nudibranch has a pair of sensory tentacles on its head called rhinophores, which are also typically orange for most of their length. These rhinophores are perfoliate, meaning they have a series of plate-like structures that increase their surface area, enhancing their ability to detect chemical cues in the water. This is crucial for helping the nudibranch find food.

Distinguishing Cockerell’s nudibranch from other local nudibranchs can sometimes be a delightful challenge for marine life enthusiasts. For instance, the clown nudibranch, also known as Triopha catalinae, is another white and orange nudibranch. While it looks remarkably similar to Cockerell’s nudibranch, it generally has fewer dorsal projections, and the orange markings can also appear on its gills and the surface of its back.

Habitat and Distribution: Where to Find Cockerell’s Nudibranch

Cockerell’s Nudibranch is a mainstay of the Eastern Pacific, with a range extending from Vancouver Island, British Columbia, down to Baja California, Mexico. Along the BC coast, it can be encountered in a variety of rocky intertidal and subtidal environments, typically to depths of around 35 meters.

Keen-eyed observers exploring tide pools during low tide or divers meticulously examining rock faces and kelp forests may be rewarded with a sighting of this colourful sea slug.

A Specialized Diner: The Role of Cockerell’s Nudibranch in BC’s Marine Food Web

Despite their delicate appearance, many nudibranchs are carnivorous. Cockerell’s nudibranch is a highly specialized predator, feeding primarily on a type of encrusting bryozoan, the orange-brown coloured Hincksina velata. Bryozoans, often mistaken for corals or seaweed, are colonial animals composed of tiny individual zooids. Using its radula, a ribbon-like tongue covered in minute teeth, Cockerell’s nudibranch meticulously rasps away the bryozoan zooids from their protective casings, leaving behind the characteristic white skeleton of the colony.

This specialized diet places Cockerell’s Nudibranch in a specific niche within the marine food web. As a primary consumer of Hincksina velata, it plays a role in controlling the population of this bryozoan. While it might seem like a small interaction, the balance between predator and prey is fundamental to the health and structure of the entire ecosystem.

Like many other nudibranchs, Cockerell’s nudibranch has few direct predators due to its effective defence mechanisms. In fact, many nudibranch species derive protective compounds from their prey. By consuming bryozoans, Cockerell’s nudibranch may accumulate chemical deterrents that make it unpalatable to larger predators such as fish or crabs. Their bright colours, a phenomenon known as aposematism, can also serve as a warning signal to potential predators, advertising distastefulness or toxicity.

Threats on the Horizon: Challenges Facing Cockerell’s Nudibranch

BC’s marine life faces a range of threats stemming from human activities and environmental changes, and the Cockerell’s nudibranch is no exception. Understanding these threats is crucial for appreciating the need for conservation efforts along the BC coast.

- Habitat Loss and Degradation: Coastal development, pollution from industrial discharge and urban runoff, and physical disturbances to intertidal and shallow subtidal zones can directly impact the rocky habitats and bryozoan colonies that Cockerell’s nudibranch depends on. Sedimentation can smother bryozoans, reducing the nudibranch’s food supply.

- Pollution: Chemical pollutants, including heavy metals, pesticides, and plastic-derived toxins, can accumulate in marine organisms. Filter-feeding bryozoans can absorb these pollutants, which can then be transferred to the nudibranchs that consume them. This can affect their health, reproductive success, and survival.

- Global Warming: Rising sea temperatures and ocean acidification, both consequences of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide, pose significant threats to marine ecosystems. Changes in water temperature can directly affect the metabolic rates, reproductive cycles, and survival of nudibranchs and their prey. It can also lead to shifts in species distribution, potentially altering predator-prey dynamics. Some nudibranch species have been observed shifting their ranges northward in response to warming waters, which can lead to increased competition with, or predation on, resident species in the new areas.

- Overfishing and Destructive Fishing Practices: While Cockerell’s nudibranch is not a commercial target, broader habitat destruction and shifts in the marine food web caused by unsustainable fishing practices can have cascading effects. For example, bottom trawling can destroy sensitive underwater habitats where these nudibranchs and their prey reside.

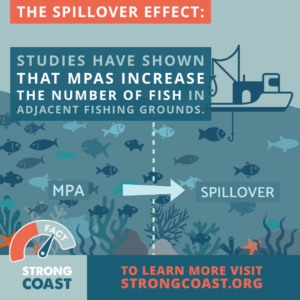

The Vital Role of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

The threats facing Cockerell’s nudibranch and the broader marine environment highlight the critical importance of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). MPAs are designated zones in the ocean where human activities are restricted to conserve natural and cultural resources. For species like Cockerell’s nudibranch, MPAs can offer several key benefits:

- Habitat Protection: MPAs can safeguard the rocky shores, kelp forests, and other critical habitats that Cockerell’s nudibranch and its bryozoan prey require. By limiting destructive activities such as certain types of fishing, dredging, and coastal development, MPAs help maintain the integrity of these habitats.

- Scientific Research and Monitoring: MPAs serve as invaluable natural laboratories. They provide baseline areas against which the impacts of human activities in unprotected areas can be compared. Research within MPAs can help scientists better understand the life histories of species like Cockerell’s nudibranch, their ecological roles, and their responses to environmental changes like global warming. This knowledge is vital for effective marine life management.

- Building Resistance to Global Warming: While MPAs cannot directly stop ocean warming or acidification, they can help marine species strengthen their ability to recover from these negative impacts. By reducing other stressors like pollution and habitat destruction, MPAs allow marine organisms and ecosystems to be in a healthier state, potentially increasing their capacity to cope with the worsening impacts of global warming.

For the residents of BC’s coast, the presence of creatures like Cockerell’s nudibranch is a reminder of the rich biodiversity that lies just offshore. These small, vibrant sea slugs are more than just a beautiful sight; they are integral components of a complex marine ecosystem.