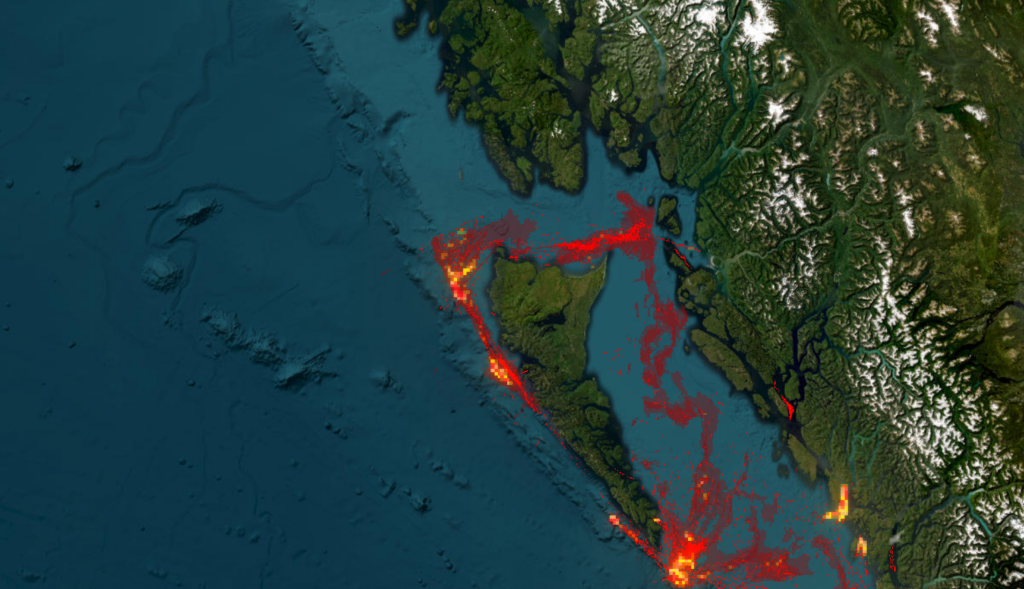

Industrial bottom trawling has long operated out of public view, but Pacific Wild’s recently released report, “Dragged to Death”, is shining a light on its scale and ecological cost. Using satellite tracking data, Pacific Wild reveals that just nine super trawlers have dragged 89,700 square kilometres of BC’s seafloor over 13 years of dragging activity. This is an area larger than the entire country of Ireland.

Which Super Trawlers Operate on BC’s Coast?

While many members of the public believe otherwise, bottom trawling is not illegal in Canada. It remains one of the most dominant fishing methods used in BC, where the groundfish trawl fishery operates year-round. While midwater trawlers are sometimes perceived as less harmful, most trawlers are licensed for both bottom and midwater trawling and can switch between methods depending on the targeted species.

In 2023, there were 41 active trawlers in BC waters; in 2024, there were 28. Of particular concern are nine large, mostly corporate-owned industrial vessels:

- Raw Spirit

- Owned by Independent Seafoods Canada Corporation (ISCC). In 2013, ISCC’s president Kelly Andersen partnered with Tracy Ronlund, Theresa Williams, and Jim Pattison‑owned Canadian Fishing Company (Canfisco) to acquire this trawler.

- Length: 44m

- Built in 1998 in Harstad, Norway.

- Retrofitted for operations in BC in 2013 to target Pacific whiting, walleye, pollock, and arrowtooth flounder.

- In 2022, Raw Spirit joined a fleet of research vessels in Alaska for a research project.

- Sunderoey

- Owned by Independent Seafoods Canada Corporation (ISCC).

- Length: 56m.

- Built in 2004 in Castropol, Spain.

- From 2004 to 2020, she operated in the European Arctic, targeting whitefish and shrimp.

- She trawls for and processes fish meal in BC.

- Northern Alliance

- Owned by Select Seafoods Canada Ltd. The company was incorporated in 2012 specifically to acquire and operate this trawler. On the company website, it says “There are five shareholders who are well known, long-time participants in the fishing industry.”

- Length: 39m.

- Built in 1990 in Gdansk, Poland.

- Fished in the North Atlantic from 1990 to 2012.

- Most likely trawled for hake, pollock, redfish, and arrowtooth flounder while in BC.

- In November 2024, she departed the West Coast for Atlantic Canada and has been fishing on the East Coast since January 2025

- Osprey No. 1

- Owned by Osprey Marine.

- Length: 57.5m.

- Built in 1998 in Frederikshawn, Denmark.

- Actively fished the North Atlantic from 1998 to 2009.

- The Osprey is used for groundfish and is equipped with a large freezer and onboard factory.

- Viking Alliance (now Pacific Alliance)

- Owned by Pacific Alliance Vessel Holdings Inc. Formerly owned by Hammer Mikkjal from Faeroe Islands. Not much is known about the current owner.

- Not to be confused with a California-based vessel of the same name, which is a workboat designed for offshore aquaculture duties.

- Length: 40.8 m.

- Built in 1996 in Wolgast, Germany.

- Was active in the production of frozen fish, shrimp, and canned cod liver in the North Atlantic from 1996 to 2018.

- The vessel is named as Ivan Shankov in a WWF-Russia report on illegal cod fishing, but no specific allegations were made.

- Pacific Legacy

- Owned by Pacific Seafood Legacy Inc.

- Length: 37m.

- Built in 2000 in Vaagland, Norway.

- Has operated throughout Europe under several names. In Norway, she was primarily used for prawn fishing.

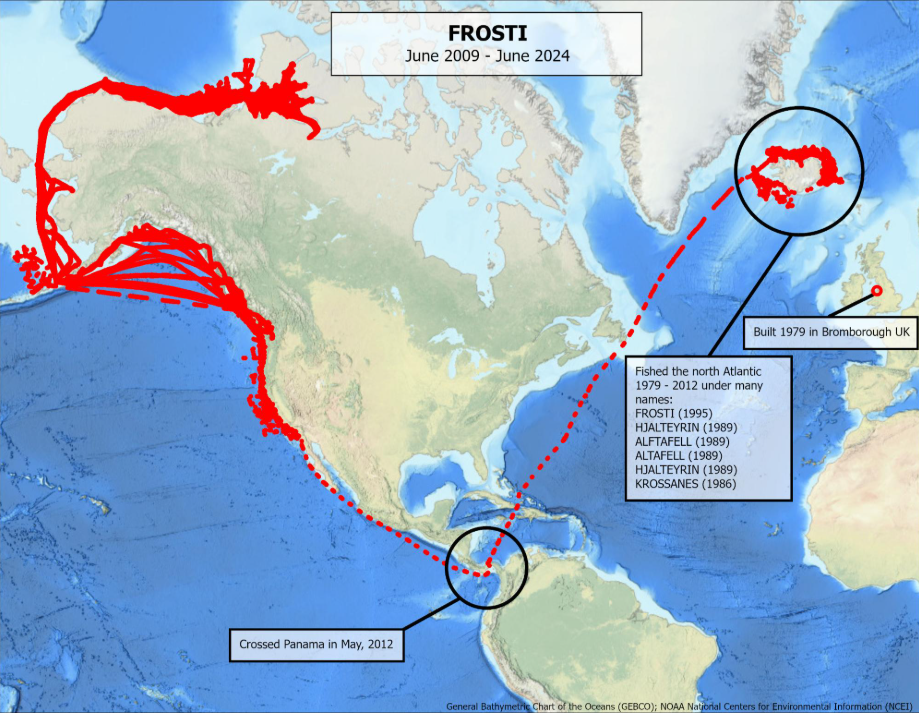

- Frosti

- Between 2016 and 2018, the vessel was co-owned by Frosti Fishing Ltd., Jim Pattison Enterprises Ltd., and Radil Bros. Fisheries Co. Ltd., all based in BC. Jim Pattison Enterprises Ltd. took over sole ownership of the vessel from 2023 to 2025.

- Active from 1979 to 2012 in the North Atlantic before arrival in BC.

- The oldest of the nine vessels.

- Length: 39.7 m.

- Built in 1979 in Bromborough, UK.

- Was used in Canada for catching groundfish like halibut, cod, and sole.

- Lingbank

- Owned by Jim Pattison Enterprises Ltd.

- The second oldest of the nine vessels.

- Length: 41.8 m.

- Built in 1985 in Flekkefjord, Norway.

- Fished in the North Sea from 1985 to 2019.

- In the North Sea, the Lingbank primarily targeted herring, sandeel, and sprat.

- Nordic Pearl

- Owned by Ocean Fisheries Ltd. and Jim Pattison Enterprises Ltd.

- Length: 34.9 m.

- Built in 1989 in Vaagland, Norway.

- Fished the North Atlantic as Broegg 1 (2002) and Broegg (2000) from 1989 to 2009.

Most of the ownership information above was obtained from DFO’s online Licensed Fishing Vessel database, except for the Northern Alliance, which was not listed in the database. DFO says that the database was last updated on June 25, 2025. The identification of these nine vessels by Pacific Wild is based on data collected up to 2024, which means a few of these vessels may no longer be operating in BC.

It is worth noting that databases other than DFO’s will still list a foreign owner for some of these vessels, with the caveat that the information could be outdated. This indicates that ownership was likely transferred as the vessels left European waters and made their way to BC. There is no clarity regarding whether any beneficial ownership arrangements are in place, where a Canadian entity effectively controls the vessel’s operations within Canadian waters, despite having a foreign legal owner. This sort of arrangement may potentially be undertaken to meet domestic flagging requirements or to integrate foreign-owned vessels into Canadian fishing quotas.

What is the Track Record of These Super Trawlers?

The Pacific Wild report raises questions about these vessels depleting fishing grounds in the UK, Norwegian Sea, Greenland, and the Bering Sea, changing their names, and sailing off to other locations like BC to continue trawling, as their operating periods coincide with severe fish stock collapses.

Vessels like the Frosti, Nordic Pearl, and Northern Alliance were engaged in commercial fishing around Iceland and Greenland during periods of decline in the cod, haddock, herring, halibut, and shrimp fisheries. By 2000, cod stocks in the region had collapsed, raising questions about whether regulatory tightening or stock depletion prompted these vessels’ move to BC.

The story is similar in Alaska, where local communities have long had a contentious relationship with trawlers. In 2016, the Chinook salmon population in Bristol Bay reached record lows, and cod stocks in the Gulf of Alaska declined by an estimated 71%.

By late 2023, NOAA Fisheries (the American equivalent of Fisheries and Oceans Canada) also confirmed that 11 killer whales were caught as bycatch by trawlers in that year alone. At least six of those killer whales perished as a result.

Despite public outcry, NOAA said, “The number of incidental takes is higher than previous years. However, it is still below the annual level that would pose a risk to the long-term health of any of the three killer whale stocks found in the region where the incidental takes occurred.”

Bottom trawling also drags heavy nets across the ocean floor, disturbing or destroying marine habitats. Studies conducted in Alaska show that a single trawl can reduce local animal abundance by over 55%, with invertebrates declining by up to 68%.

Overlap with Chinook Migration and Bycatch Concerns

The report also highlights that trawler pathways nearly perfectly overlap with the migration routes of Chinook salmon. A 2022–2023 enhanced monitoring program by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) found that groundfish trawlers unintentionally caught nearly 30,000 salmon in a period of about four to six months. Of the wild salmon caught as bycatch, 93% were Chinook. Over a broader timeframe, from 2008 to 2023, more than 140,000 salmon were caught as bycatch, with Chinook again making up 89% of the total.

These bycatch figures are significant, as Chinook are a critical food source for endangered Southern Resident killer whales.

“The number of Chinook caught in that timeframe could have sustained 17 critically endangered Southern Resident Killer Whales for an entire year,” the Pacific Wild report stated.

On top of that, the DFO’s report also revealed that salmon bycatch rates were 78% to 710% higher than previously detected under standard monitoring methods.

Trawling in BC has come under scrutiny for reports of observer intimidation, which whistleblowers painted as an attempt to force the underreporting of bycatch. A months‑long investigation by The Narwhal based on interviews with 11 current and former at‑sea observers found that workplace intimidation and harassment on BC industrial trawlers have led to an estimated 140 million pounds of bycatch not being reported in 20 years. One observer described witnessing the Raw Spirit discard an estimated 50,000 pounds of halibut in just three-and-a-half days, though only a fraction was officially recorded.

What is the Impact of Trawling in BC?

A 2007 study found that 97% of the seafloor along the west coast of Vancouver Island, at depths between 150 and 1,200 metres, had been contacted by bottom-trawl gear. However, this assessment only covered a portion of the coast and was conducted before the arrival of the nine large super trawlers that now dominate much of the offshore fishery.

Further research from Pacific Wild found that between June 2009 and June 2024, these nine super trawlers collectively travelled 907,680 kilometres. This is equivalent to circling the planet more than 22 times. This estimation does not include the 30 to 40 other smaller trawlers currently operating in BC waters, nor any trawl activity predating the satellite tracking period.

Pacific Wild found that trawlers frequently intersect with sensitive geological features, such as seamounts —underwater mountains that rise from the ocean floor. There may be as many as 50,000 seamounts taller than 1,000 metres in the Pacific Ocean, yet most remain unprotected and vulnerable to trawling impacts.

Glass sponge reefs, another vulnerable habitat, are also under threat. Some of these reefs on the BC are over 9,000 years old. Scientists estimate that half of the reefs had already been damaged by bottom trawling before they were even discovered in 1987. In addition, bottom trawling activity can stir up sediments that suffocate and choke sponge colonies up to six kilometres away. This causes the sponges to not be able to feed for six to twelve hours. If this happens often enough, the sponges will die.

Deep-sea habitats, such as sponge reefs and seamounts, may take centuries to recover, and many will not recover at all. These habitats are home to slow-growing or fragile species like deep-sea corals, long-lived rockfish, brittle stars, basket stars, and sea pens.

The Impact of Trawling on Coastal Communities

Unlike smaller trawlers, these “super trawlers” carry onboard processing facilities and can remain at sea for longer periods, catching and freezing fish on board. Their industrial scale and high catch volumes mean their ecological impact is outsized.

In BC, the high cost of licences and quota has pushed small-scale and Indigenous fishers out of the commercial trawl sector. Processing companies are allowed to own fishing licences, and these can be traded like stocks. This market structure concentrates access in the hands of corporations with the capital to acquire quota, leaving little room for community-based fishing.

“In British Columbia, corporations are some of the only entities left that can afford to own fishing licenses and quota,” the report stated. According to DFO’s 2022 report on commercial licences and quota values, the average groundfish-trawl licence (T Licence) in the Pacific Region had a total value of CAD $5.5 million per licence, which includes both licence and quota holdings.

A DFO report from 2022 named The Canadian Fishing Company, owned by BC fisheries magnate Jim Pattison, as the company with the most commercial fishing licences on our coast. They own 234 licences across multiple fisheries.

Disputing the Industry Narrative

Ray Hilborn, a professor at the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, and Bruce Turris, former executive manager of the Canadian Groundfish Research and Conservation Society, have defended trawling as limited in impact.

Hilborn claimed that “the same 5% of B.C.’s bottom habitat […] is trawled year after year.” Turris compared trawling to “paving a road,” suggesting the damage is confined to previously impacted zones. However, Pacific Wild’s data challenges these claims. Their analysis reveals that trawling activity is consistently concentrated in ecologically rich zones, such as seamounts, shelf breaks, and salmon migration corridors, rather than in degraded areas.

“These zones are the “breadbaskets” of the coast, serving as critical breeding, nursery, and feeding grounds for a wide range of marine life,” the report states.

“Bottom trawling is a ghastly process that brings untold damage to sea beds that support ocean life. It’s akin to using a bulldozer to catch a butterfly. We wouldn’t do this on land, so why do it in the oceans?” said marine biologist Dr. Sylvia Earle in her 2013 article “Can We Stop Killing Our Oceans Now, Please?”

Lack of Transparency and Data Access

Much of the vessel movement data in Dragged to Death had to be purchased from private providers, as detailed trawl data is not readily available from DFO.

GIS analyst Kevin Lester, who worked on the mapping project, noted: “All of this was built upon the first objective, which is just trying to get the data, which shouldn’t be so hard, given that these vessels have a massive impact on the BC coast and should be kept track of in a more public data set.”

Pacific Wild also stated that DFO, when asked, refused to release the names of vessels trawling BC’s coast before 2025, citing privacy concerns.

Can Marine Protected Areas Combat Trawling in BC?

Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are a key tool for safeguarding biodiversity from industrial impacts. In 2019, Canada adopted minimum protection standards for MPAs, including prohibitions on bottom trawling, oil and gas activities, mining, and dumping. However, the MPAs that predate these standards do not yet have full enforcement in place.

SAUP-5494, a biologically rich seamount off the west coast of Haida Gwaii, has been identified for protection as the only seamount present in the upcoming Great Bear Sea MPA network. This area is characterized by unique features that create ideal conditions for a diverse array of marine species.

“SAUP-5494 supports a wide array of life, including fish species like Longspine Thornyhead, Shortraker and Shortspine Thornyhead, Darkblotched Rockfish, Widow Rockfish, as well as groundfish such as Pacific Ocean Perch, Rex Sole, Sablefish, and Pacific Halibut,” Pacific Wild’s report said.

“It also serves as an essential habitat for whales, including Sperm, Sei, Blue, Fin, and Humpback, as well as Albatrosses and deep-sea corals.”

The Great Bear Sea MPA network will prohibit bottom trawling activities upon implementation.

As pressure mounts to meet Canada’s ocean protection targets and reverse the population decline of key species on our coast, advocates say stronger restrictions, public transparency, and habitat-specific safeguards will be essential to reforming the fishery and protecting the ecosystems that underpin it.