Armed with a camera, a notebook, and persistence, Ryan Michael is reshaping how the coast thinks about whales, tourism, and the waters they call home.

A Circus at Sea

The orcas move like shadows beneath the waterline, their dorsal fins slicing the surface of Haro Strait. Midsummer light bends off the water in silver sheets. From the cliffs above, the sight is captivating: a matriarch and her pod threading their way past kelp beds, each breath a thunderclap on the glassy sea.

But the silence does not last. Engines arrive: first a hum, then a roar, then a flotilla, churning whitewater in their scramble to flank the pod. If the whales turn, the boats turn. If they dive, the boats idle and wait. The whales have no break, no sanctuary.

For Ryan Michael, a land-based whale watcher who spends between 30 and 40 hours a week tracking whales from the cliffs and coves of southern Vancouver Island, the spectacle is both heartbreaking and galvanizing. “They are intelligent beings with no voice and no reprieve,” he says. What the marine tourism industry once sold as conservation and education has tipped into relentless pursuit, a circus at sea.

From Toronto Streets to Vancouver Island

Ryan grew up in Toronto’s concrete maze, far from the Pacific, but summers on Vancouver Island left a mark. The chance to return came in 2020 after COVID lockdowns pushed him to relocate to Victoria.

His background in media meant he was already trained to watch, document, and tell stories. That skill turned seaward when he began covering the fate of Brave Little Hunter, a transient orca calf who became trapped in Zeballos lagoon after her mother drowned. “Brave Little Hunter and her grandmother’s pod (T109As) will always hold a special place in my heart,” he says.

His attachment deepened with the T109As. But joy turned to outrage as he continued to witness more marine tourism violations and a culture of whale-hounding.

Reality Check: When Tourism Becomes Pursuit

By summer, the Salish Sea feels less like a sanctuary and more like a freeway. Dozens of vessels crisscross the waters, chasing close encounters. Hundreds of tourists can surround whales from sunrise to sunset.

Marine tourism was once framed as conservation through experience, a belief that seeing whales inspired protection. In recent decades, whale watching has been hailed as a sustainable activity. But now the industry is a multi-million-dollar enterprise on both sides of the border, and with growth comes mounting pressure on the very species it claims to safeguard.

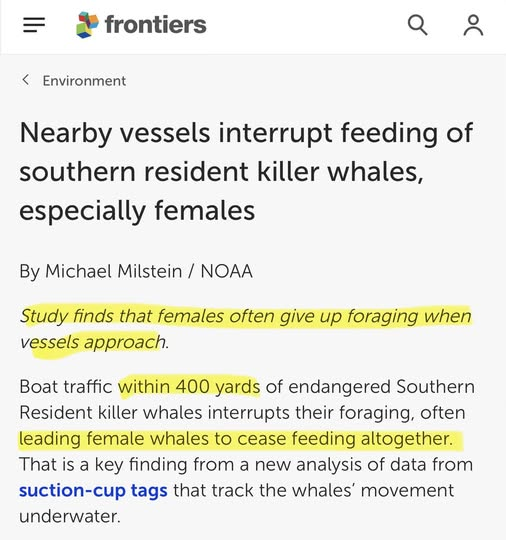

Studies have found that vessel traffic interrupts critical whale behaviours. Noise from boat engines masks the echolocation Southern Resident killer whales rely on to hunt salmon. Whales call louder when vessels are near, a stress response that demands more energy. Vessel disturbance is also linked to reduced foraging success, with whales abandoning hunts to avoid increasing underwater noise. Over time, these repeated disruptions cut into their already precarious energy budget and are a contributing factor to the Southern Resident’s endangered status.

Weak Rules, Weaker Enforcement

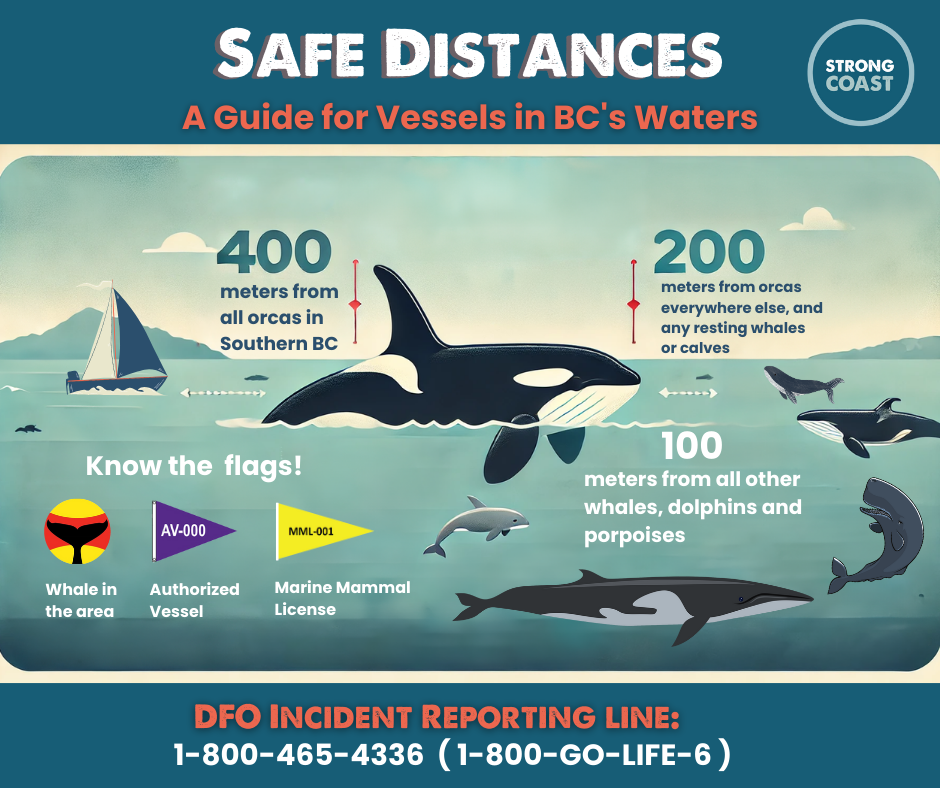

On paper, Canada’s rules require vessels to stay 100 meters from most cetaceans and 200 meters from killer whales; for Southern Residents, it’s 400 meters in summer. Yet Ryan argues these distances are insufficient, especially for struggling populations. “We know that anything under 400 meters, they can’t find their food,” he says.

Science supports Ryan’s concern. A 2019 review by Fisheries and Oceans Canada confirmed that vessel noise can mask killer whale echolocation clicks at even greater distances. Repeated close approaches increase whale stress, impacting reproduction and calf survival.

Yet regulation means little without enforcement. On the water, oversight is almost nonexistent. “Straitwatch is incredible,” Ryan says, referring to the small nonprofit that patrols local waters and educates boaters. However, with only one vessel patrolling, monitoring dozens of operators is impossible. Federal officers are overwhelmed and underfunded. The absence of meaningful monitoring leads to self-policing, often resulting in companies defending one another instead of holding each other accountable.

Noisy Neighbours: American Vessels

American vessels often make the situation worse. “They’re the loudest and most relentless in the Salish Sea,” Ryan says. Sometimes, they’re the only sound in supposed prime feeding grounds for Southern Residents.

When many vessels converge on a pod, the pressure multiplies, harming the animals. Yet American companies continue to market Canadian waters as conservation-friendly, often at steep prices. But instead of conservation, these vessels contribute to endangerment.

A Digital Chase: Sightings and Social Media

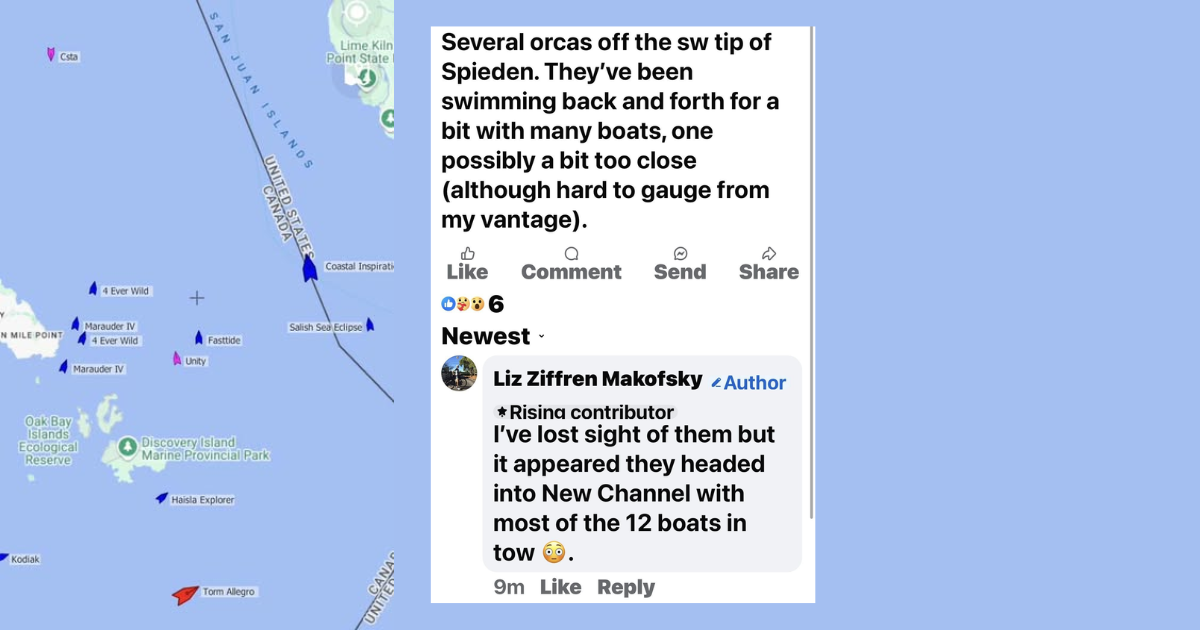

Increasingly, the chase begins online. Sightings posted in Facebook groups become instant signals for tour operators. When Ryan began documenting whales on the Comox Valley Wildlife Sightings page, he realized reports were funnelled to commercial operators.

Disillusioned, he launched Friends of Vancouver Island Whales, where membership is tightly controlled to keep sightings from the industry.

The group now has nearly 17,000 members, mostly women. To Ryan, it’s proof that ethical, land-based whale watching resonates with those who want to witness whales without feeding the chase.

Marketing the Myth

One of the most damaging aspects of the industry is how it’s sold to the public. Companies market close encounters as conservation, education, and even ethics. The Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA) boasts “the best standards in the world.”

But Ryan calls this branding an illusion. Guaranteed sightings fuel the chase, reducing whales to entertainment. Land-based watching offers no guarantees; it demands patience and knowledge.

Vessel accountability is another gap. Many operators don’t keep their Automatic Identification System (AIS) on. From land, Ryan counts more boats working a pod than appear on AIS. If accountability mattered, AIS would be mandatory.

Conservation claims remain central to marketing, yet most companies donate less than 1% of their revenue to actual conservation efforts. For Ryan, the hypocrisy is clear: whales have become a business model, one that thrives on intimacy while masking the cost to these magnificent creatures.

Industry Pushback and Personal Risk

Exposing these practices hasn’t come without personal risk. Ryan faces pushback from tour operators. Online forums often shut down debate the moment someone points out infractions. Independent voices like his are vital and vulnerable.

Herded Offshore

Ryan has witnessed a disturbing shift: vessels don’t just trail whales, they appear to steer them. When orcas come close to shore, distances are obvious and harder for boats to hide. But after Ryan began documenting vessel behaviour, close shoreline encounters vanished.

Instead, vessels now coordinate formations farther offshore, effectively herding whales and making oversight harder.

Hope on the Horizon

Despite the frustration, Ryan insists he isn’t opposed to whale watching, but to the industry model that equates harassment with conservation. Ethical whale watching would mean dramatically scaling down operations. The first step, he argues, is removing American vessels from Canadian waters. Real enforcement backed by funding for oversight agencies and independent monitors is essential.

Ryan’s optimism is grounded in people, not policy. Coastal residents are now aware of the problem due to his reporting. Some vow never to board whale-watching vessels again, opting instead for land-based watching. Each message is proof: awareness sparks change.

True reform won’t happen overnight, but the vision is clear: a coast where whales are observed respectfully, where conservation is more than a marketing slogan.

Drawing the Line

Whale watching is sold as awe and wonder: a chance to glimpse giants in the wild. But behind glossy brochures lies an industry that too often treats whales as attractions, not neighbours worthy of respect.

Respectful tourism isn’t about denying whale encounters; it’s about choosing where they take place. On bluffs and beaches, with binoculars and patience, the magic is still there, without intruding on the whales’ world.

His commitment to this cause extends beyond observation. This summer, he invested in a new camera to sharpen his documentation of vessel behaviour. In the quieter winter months, he hopes to take the next step: collaborating with filmmakers to turn his footage and reporting into a documentary. For him, this work is a long-term commitment. “At the end of the day, I’ll keep going until something changes,” he says.

Ryan Michael is more than a whale watcher. He’s a citizen witness, a voice for animals, and a reminder that conservation begins with accountability. His work challenges us all to draw our line in the water, prioritizing survival over spectacle, respect over revenue.

Ultimately, he believes the strength to protect these whales will come from many, not one. “We’re stronger together.” On this coast, that collective power is what the whales most need.