The Fraser River’s unexpectedly strong sockeye salmon returns this year have renewed calls to accelerate the removal of open-net fish farms from BC’s coastal waters.

Marine scientists, First Nations leaders, and wild salmon experts say the surge, with some runs six times higher than forecast, is evidence that removing fish farms from key migration routes can help wild salmon rebound.

But with the federal government now delaying a full phase-out until 2029, experts warn that these gains could be short-lived.

As of August 11, Fisheries and Oceans Canada issued a notice allowing recreational fishers to keep two sockeye per day, fishing only a non-tidal stretch of the river from the Mission Bridge to Hope until Sept 1.

Closing Farms, Seeing Results

After years of pressure from First Nations and wild salmon researchers, the federal government started removing fish farms from critical migration routes. Since 2019, more than 40 farms have been shut down in the Broughton Archipelago and Discovery Islands.

This year’s sockeye returns are the same populations that migrated to sea after many of these closures. While ocean conditions, landslide repairs, and enhancement programs also play a role, marine biologist Alexandra Morton says the correlation is too strong to ignore.

“The fish that are coming back this year are the same family of fish that went missing in 2009,” Morton said. “I think this is probably the most successful government environmental policy ever.”

Fish Farms in BC: A Breeding Ground for Problems

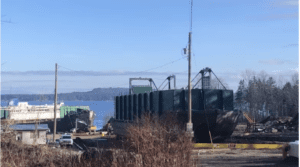

BC’s open-net pen salmon farms, first established in the 1980s, hold hundreds of thousands of Atlantic salmon in floating cages directly in the ocean. Because the nets allow water and everything in it to pass freely, they create an ideal environment for parasites and pathogens to increase and spread to wild fish swimming past.

Over the decades, these farms have been placed directly along major migration corridors for Fraser River sockeye, Chinook, and other Pacific salmon species, especially in the Discovery Islands and Broughton Archipelago.

The most notorious threat is the parasitic salmon louse, a small crustacean that feeds on salmon skin, mucus, and blood. In the wild, lice are naturally present, but in low densities that rarely harm adult salmon. This is where the argument

On fish farms, however, lice infestations can reach levels hundreds of times higher than in the open ocean, turning the farms into parasite reservoirs. Juvenile wild salmon migrating past farms are particularly vulnerable.

A 2021 peer-reviewed analysis of BC salmon farms found that farm-adjacent juvenile salmon had salmon lice infestation rates up to nine times higher than those migrating through farm-free areas. In peak outbreak years, over 90% of sampled juvenile salmon near farms were infected. Such rates are far above the Fisheries and Oceans Canada own threshold for harm.

The Delayed Exit

Originally promised for 2025, the phase-out of all open-net pen fish farms in BC has been pushed back to 2029. Former Federal Fisheries Minister Diane Lebouthillier says the extension is to allow industry to transition to closed-containment or land-based systems. But critics fear the delay means four more years of exposure for young salmon to parasite outbreaks, viral transmission, and population losses.

The fish farm industry continues to assert that there is no link between salmon farms and the wild salmon decline. However, critics argue that much of the science cited by the industry may be compromised by conflicts of interest or lacks rigorous peer review. For example, a 2023 report provoked strong backlash from academics: over a dozen university-based scientists from institutions such as UBC, University of Toronto, Simon Fraser, and University of Victoria publicly condemned it for “serious scientific failings,” arguing it fell short of credible, peer-reviewed standards.