Glass sponge reefs were believed to have become extinct 40 million years ago. However, in 1984, Glen Dennison discovered them in the depths of Howe Sound while researching his book on diving.

His discovery launched a private citizen effort to locate and protect the reefs, eventually resulting in the DFO protecting seventeen different sites in Howe Sound and the Hecate Strait. The three reefs within the Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound Marine Protected Area cover 1000 km2.

How Glass Sponge Reef Ecosystems Form

The formation of these reefs begins with the growth of living glass sponges, which possess skeletons made of silica, giving them their characteristic “glass” appearance. These sponges thrive in deep, cold, and nutrient-rich waters, such as those found in British Columbia, at depths ranging from 100 to 300 meters. The specific environmental conditions necessary for their survival include stable temperatures, a rigid substrate for attachment, and a sufficient flow of water to filter feed on plankton and organic particles.

When glass sponges die, their silica skeletons remain on the seafloor, gradually accumulating into layers of siliceous material. Over time, this material compacts and binds together, often with the assistance of organic matter, creating a solid foundation for future growth. New generations of glass sponges grow on top of these remains, leading to the gradual buildup of layers and the forming of a reef structure. The skeletal remains become cemented together, sometimes aided by microbial activity and sedimentation, resulting in a stable structure that supports further growth.

As the reef matures, it becomes a habitat for diverse marine species, including fish, invertebrates, and other organisms that find refuge within its complex structure. Mature glass sponge reefs contribute to the stability of the surrounding marine environment by providing habitat, filtering large volumes of water, and influencing local nutrient cycles. The process of reef formation is ongoing as long as environmental conditions remain favourable, allowing the reef to expand vertically and horizontally over time. These reefs, which can grow to cover large areas of the seafloor, are among the most ancient and biologically diverse habitats in the ocean.

What Role Do Glass Sponges Play in a Marine Ecosystem

Glass sponge reefs play several vital roles in the marine ecosystem.

1. Habitat Formation: Glass sponges provide habitat and shelter for various marine organisms, including small fish, shrimp, and other invertebrates. The complex architecture of glass sponge reefs offers protection from predation and serves as a substrate for attachment and colonization.

2. Filter Feeding: Glass sponges are exceptional filter feeders capable of filtering large volumes of seawater. As they pump water through their bodies to extract food particles like bacteria and plankton, they help maintain water quality by removing excess organic material and microscopic organisms. This filtration process also contributes to nutrient cycling in the ecosystem, as the sponges release filtered, nutrient-rich water back into the environment.

3. Calcium, Carbon, and Silica Cycling: Glass sponges absorb and incorporate calcium carbonate from seawater into their spicules. When these sponges die and their spicules settle on the seafloor, they contribute to calcium cycling in the ecosystem. This process can have positive implications for the overall carbonate chemistry of the ocean.

4. Biodiversity Support: Glass sponge reefs increase local biodiversity by providing a unique environment that supports a wide range of species. These reefs offer shelter and feeding opportunities for various fish, crustaceans, mollusks, and other invertebrates, many of which are specially adapted to live in the specific conditions the reef provides. This diversity of life contributes to the overall health and resilience of the marine ecosystem.

5. Ecosystem Stabilization: By providing habitat, filtering water, and cycling nutrients, glass sponges contribute to the overall stability of the marine ecosystem. Their reefs create zones of ecological productivity in otherwise barren deep-sea environments, supporting food webs and enhancing the resilience of marine communities to environmental changes.

6. Scientific and Conservation Value: Beyond their ecological roles, glass sponge reefs have significant scientific value as they offer insights into ancient marine ecosystems. Their preservation is crucial for studying the evolution of marine life and the historical conditions of the ocean. Conservation efforts to protect these reefs are essential for maintaining the biodiversity and ecological functions they support, especially given their sensitivity to disturbances like trawling and climate change.

Glass sponges, with their filter-feeding behaviour, habitat provision, ecosystem support, and role in nutrient cycling, contribute to the overall health and functioning of marine ecosystems, particularly in deep-sea environments where they are commonly found. Conservation efforts to protect these unique and vulnerable organisms and their habitats are essential for maintaining the ecological balance of these ecosystems.

“To see how the reefs looked even 10 years ago. It is really sad to see the images we are witnessing when we go down there [now].”

Tori Preddy, Marine Life Sanctuaries Society

Why are Glass Sponge Reefs Still Under Threat?

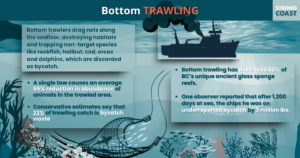

Prior to DFO protecting glass sponge reefs in BC waters, 50% of the reefs were damaged or destroyed by bottom trawling. However, despite the current protections in place, glass sponge reefs continue to be damaged by human activity. One cause of damage is poachers’ continued use of prawn and crab traps in these protected areas. Poachers who drop their traps right onto the reefs are destroying nine thousand years of nature’s work in a millisecond. Even if a dropped trap does not directly hit glass sponges, the sediment kicked up will suffocate them.

“We cannot enforce on destruction. That means that you can’t wait till someone drops a trap down there and hope that you’re going to give them a ticket or take away their gear. The reefs will be gone.”

Glen Dennison, Marine Life Sanctuaries Society

“The DFO enforcement officers are doing the best job they possibly can out there. But they are so short-staffed that they just cannot protect the sound properly.”

Glen Dennison, Marine Life Sanctuaries Society

The fact that protected reefs are damaged by illegal trapping indicates the DFO does not have the resources to monitor the protected areas properly. Moreover, while bottom-contact fishing is banned in these protected zones, anchor dropping is not, which means it is not illegal to drop an anchor and obliterate nine thousand years of nature’s work. The only way the glass sponge reefs on the Great Bear Coast will be adequately protected is by establishing the Great Bear Sea Marine Protected Area Network, which will include vigilant monitoring through Coastal First Nations’ guardians and enhanced punishment for those callous enough to destroy these ancient wonders.