Fishing vessels around the world are routinely “going dark” by turning off their automatic identification system (AIS) transponders – and British Columbia’s trawler fleet is no exception.

This has allowed industrial trawlers to operate out of sight in sensitive habitats, encouraging a pattern of exploitation along our coast.

What Are AIS Transponders and Why They Matter

AIS, or Automatic Identification System, is a shipboard broadcast tool originally designed to prevent collisions at sea. It transmits a vessel’s location, identity, speed, and direction. AIS data can be used to provide information about global fishing activity, including signs of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing.

But there’s a catch: AIS can be switched off, allowing for a different type of catch – illegal catch.

When a vessel disables its AIS transponders, it goes dark and vanishes from public view. With no signal, it can fish, move, or slip across boundaries unnoticed—and it’s not just happening overseas. It’s also happening right here, off our coast.

A Global Pattern of Vessels Going Dark

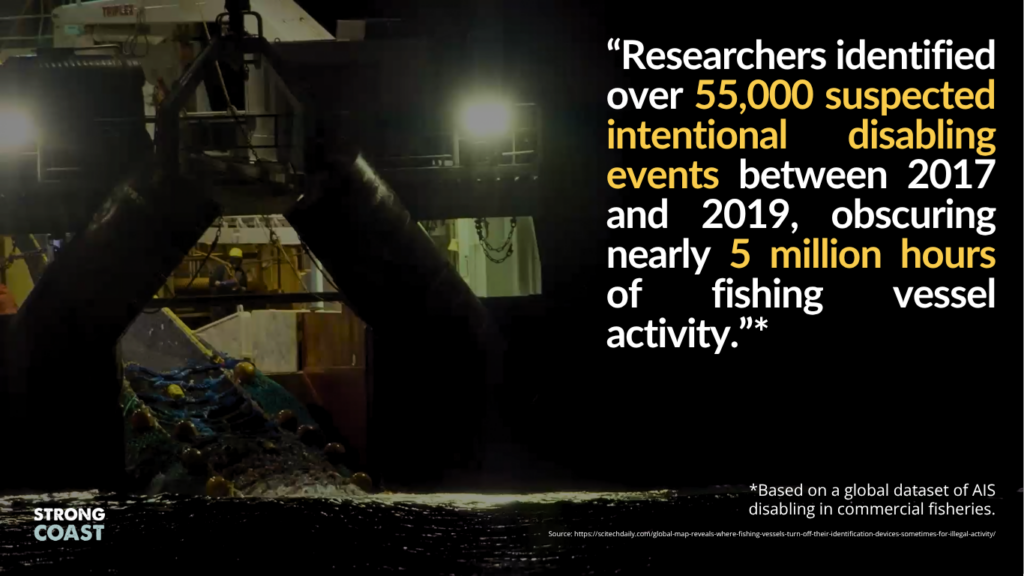

A 2022 study published in Science Advances tracked over 55,000 suspected AIS disabling events around the world between 2017 and 2019. That’s nearly 5 million hours of fishing in the dark.

There are many reasons why a vessel turns its AIS off. From avoiding pirates to hiding fishing hotspots from competitors, some motives may not be harmful to our coast.

But other reasons are far more troubling. AIS can be disabled to fish in unauthorized areas. It can also be disabled to conceal illegal transshipments, where catch is quietly offloaded onto giant freezer ships. It’s a tactic used to dodge inspections, launder fish, or, in some jurisdictions, keep crews out at sea for months, sometimes under forced labour.

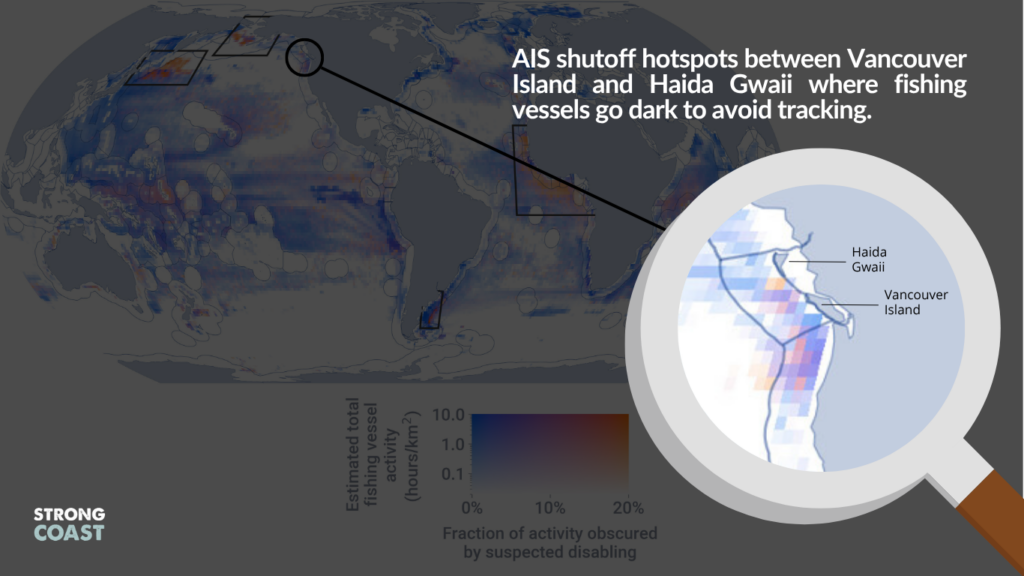

According to the same study, the waters between Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii show up as AIS disabling hotspots—similar to regions near Argentina, West Africa, and the Northwest Pacific.

The map above shows clusters of red zones off our coast, representing vessels turning off their AIS transponders on a regular basis. These are not empty stretches of ocean. They’re nurseries for groundfish and halibut. They’re home to glass sponge reefs and coral beds that support entire food webs.

If trawlers are strictly regulated, why hide?

And if these areas are supposedly protected, why are boats allowed to disappear inside them?

The “Tight Regulation” Myth

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and industry groups often call BC’s commercial trawl fishery “one of the most heavily regulated fisheries in the world.” On paper, that may be true.

But in practice?

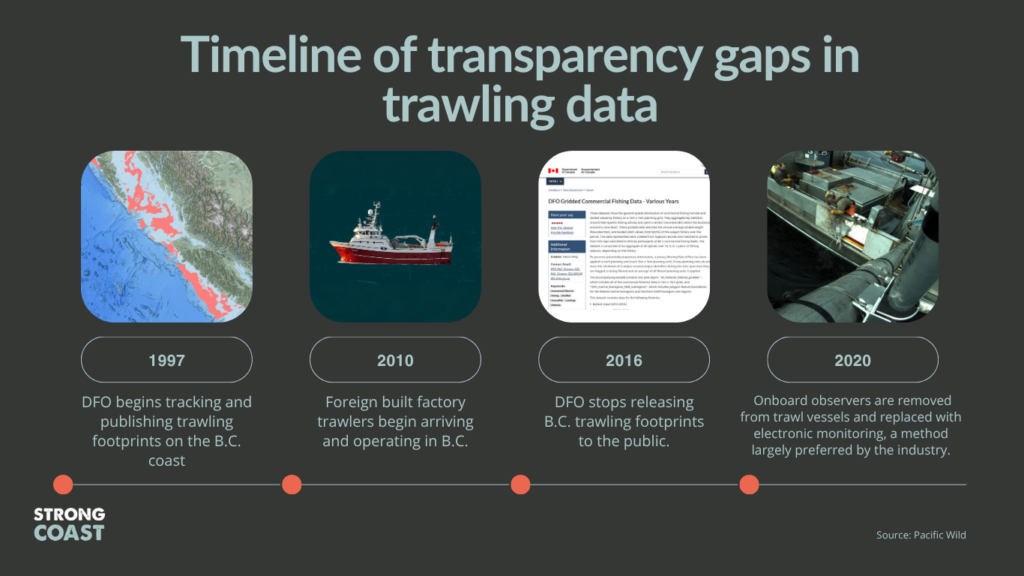

DFO stopped publicly releasing BC trawling footprints to the public after 2016. Organizations like Pacific Wild have had to buy expensive AIS data from hard-to-reach companies to understand what’s happening offshore.

Yes, vessels carry another tracking system—Vessel Monitoring Systems (VMS)—a separate tracking tool monitored by flag states. But unlike AIS, VMS data is not publicly available and is often tightly controlled by national governments. This means that while regulators might see the movement, coastal communities, researchers, and nearby vessels remain in the dark, making AIS disabling an effective way to avoid detection.

Without public access or independent oversight, the claim of tight regulation doesn’t hold water.

What Accountability Looks Like

To rebuild trust and protect BC’s coastal ecosystems, transparency is key. That means:

– Restoring public access to vessel location and records of trawl activity

– Mandatory AIS transparency, with penalties for vessels that go dark without cause

– Enforcing no-trawl zones, especially in ecologically sensitive regions

Most importantly, it means establishing the trawler-free Great Bear Sea Marine Protected Area (MPA) Network.

These waters have fed our communities for thousands of years, and they deserve more than paper promises. Let’s not wait until the damage is done to wish that we had acted sooner.