Indigenous cultures have sustainably harnessed natural resources since time immemorial. Their relationship with BC’s environment is founded on a principle of give and take, instead of just take.

Today our local marine economy is at risk due to population collapses of key marine species. It is amidst these challenges that Indigenous methods of conservation are emerging as key solutions to help revitalize our environment and keep our resource-dependent economy strong. Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) are a powerful tool to provide important economic opportunities for coastal communities, and safeguard BC’s marine economy for all by protecting BC’s most vital habitats and species. Therefore, IPCAs benefit everyone in British Columbia.

What are Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas?

An Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area (IPCA) is a protected area of land or water identified and managed by Indigenous communities. The main goals are to protect and conserve biodiversity, cultural heritage, and traditional practices. What sets IPCAs apart from other protected areas is that they are Indigenous-led, represent a long-term commitment to conservation, and elevate Indigenous rights and responsibilities.

Through extensive community planning, Indigenous governments set the boundaries and management plans of IPCAs. These plans integrate Indigenous knowledge, governance, and stewardship practices with the help of Indigenous Guardian Watchmen, who patrol the protected areas. As IPCAs set out to help defend BC’s lands and waters from industrial encroachment and overexploitation, they are also key tools in supporting Indigenous self-determination.

Why Does BC Need IPCAs?

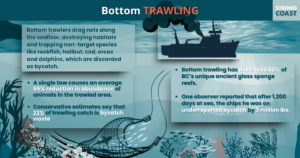

In a 2023 survey, 93% of BC residents named marine conservation as a key priority for BC’s marine economy. So what issues were they hoping that conservation would address? For 92% of respondents, “declining fish stocks” was the top priority, followed by “open-net fish farms” (90%) and “bottom trawling” (90%).

IPCAs are an excellent tool for addressing these types of threats, as they focus on sustainability. By promoting sustainable land and water management practices, supporting biodiversity conservation, and mitigating climate change impacts, IPCAs protect the marine resources critical to BC’s prosperity, which is beneficial for everyone on the coast and across the province.

Benefits of IPCAs

IPCAs create economic opportunities. An example of this can be found in the Great Bear Rainforest. Since its creation, more than 1,000 permanent jobs in sustainable sectors of the economy, such as tourism, land management, and guardianship, have been created. In addition, more than 100 local businesses have been established or experienced significant growth.

An example of the positive impact IPCAs have on tourism is the Kitasoo/Xai’Xais’ Spirit Bear Lodge within the Great Bear Rainforest, which employs nearly 10% of the local population. Profits from the Lodge are reinvested in cultural programs, business development, and a research foundation that has helped attract further investment.

IPCAs also have demonstrated an ecological impact. Salmon in BC’s Fraser watershed have been in steep decline–2020 saw the lowest run of Sockeye salmon ever recorded, and the spawn numbers of Chinook decreased from 3,500 in the 1960s to as low as 75 for some Chinook populations in 2018. This decline has been mitigated by a collaborative restoration plan led by the Katzie First Nation. This plan helped restore spawning and rearing habitat, remove river blockages, and reconnect salmon migratory routes. Strong salmon populations are essential for the health of BC waters and the prosperity for BC’s coastal communities. Therefore, this is another example of how IPCAs benefit everyone.

IPCAs in BC

British Columbia is home to several IPCAs, each with unique characteristics and contributions to conservation. IPCAs in BC safeguard not only flora and fauna but also sacred sites, traditional territories, and cultural practices of Indigenous communities.

Some of BC’s IPCAs include:

1. Haida Gwaii protected areas

The Council of the Haida Nation and the Province of British Columbia agreed to protect 18 sites within traditional Haida Gwaii territory, comprising 332,992 hectares of upland and 169,652 hectares of marine foreshore, totalling 502,644 hectares. Within this, the Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve is home to a diverse range of species, including marine mammals like humpback whales, orcas, and sea otters, as well as numerous species of fish, seabirds, and intertidal organisms. An estimated 750,000 seabirds nest along the shoreline of Gwaii Haanas from May through August. Many are burrow-nesters, such as the rhinoceros auklet, ancient murrelet, and tufted puffin.

2. Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks

The Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks encompass marine areas along the west coast of Vancouver Island including portions of the Clayoquot Sound UNESCO Biosphere Reserve. In 1984, Tla-o-qui-aht Ha’wiih (hereditary chiefs) declared Meares Island a Tribal Park in response to unsustainable logging practices. Four tribal parks fall under this IPCA: Meares Island, Ha`uukmin (Kennedy Lake Watershed), Tranquil Tribal Park, and Esowista Tribal Park.

3. Dasiqox Tribal Park (Nexwagweẑʔan)

This tribal park is located in traditional Tsilhqot’in territory in BC’s south-central interior. It covers approximately 300,000 hectares of land. The park was declared in 2014, following 25 years of legal action by the Tsilhqot’in to gain recognition of their title and rights from the Crown. The tribal park includes the Dasiqox headwaters—essential water sources for the area’s rivers, streams, lakes, salmon, fish, and other wildlife.

Challenges Faced by IPCAs:

Despite their importance, IPCAs encounter challenges, including encroachment from extractive industries, insufficient legal recognition, and inadequate support for Indigenous governance structures.

Unfortunately, many government actions are provign to be unhelpful. For instance, governments continue to greenlight industrial activities, including logging, mining, and fish farming inside IPCAs, disregarding Indigenous authority and sovereignty.

Learn more about this key challenge here.

The Future of IPCAs

Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in British Columbia represent a holistic approach to conservation, blending ecological stewardship with cultural heritage preservation. This approach safeguards biodiversity and contributes to Reconciliation, sustainable economic development, and environmental resilience. With British Columbains striving to build a more inclusive and sustainable future, IPCAs should play a central role in making this happen.