A single marine heatwave between 2014 and 2016, known as “The Blob,” wiped out an estimated four million common murres on the West Coast.

This catastrophic event, triggered by record-high ocean temperatures, is described as the largest wildlife mortality event of its kind in modern history.

The findings, published Thursday in Science, highlight how the heat wave—the most severe ever recorded in the northeast Pacific—disrupted the availability of fish species critical to the murres’ diet. The other species affected by the heat wave have also not shown any signs of rebounding.

Lead author Heather Renner of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge explained that the event’s magnitude and long-lasting consequences signal alarming shifts in the region’s ecology. “To our knowledge, this is the largest mortality event of any wildlife species reported during the modern era,” Renner stated, calling the findings a stark warning as climate change drives increasingly frequent and intense heat waves.

A Catastrophe of Unimaginable Scale

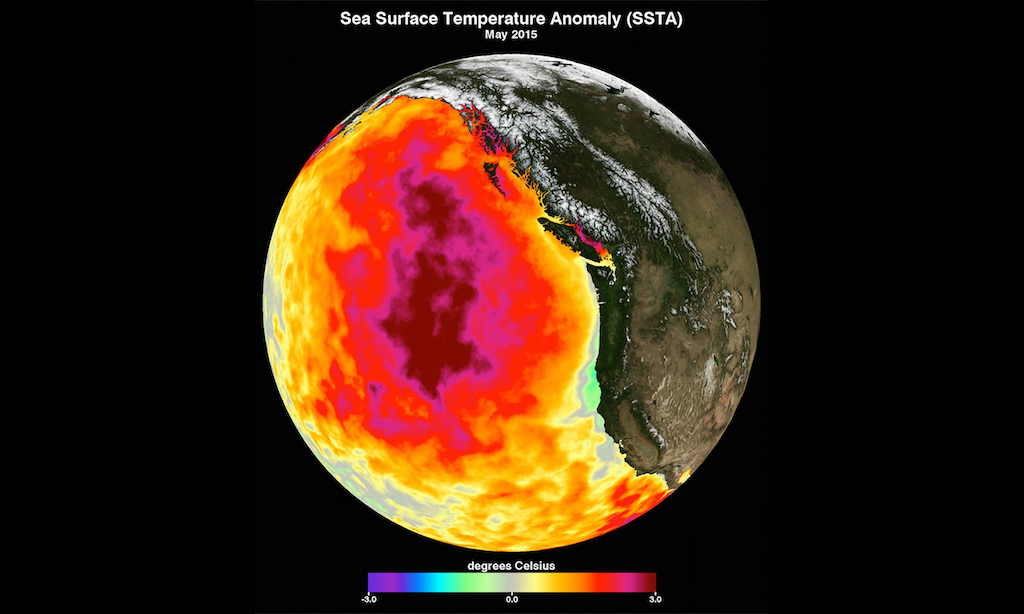

Between 2014 and 2016, the northeast Pacific Ocean experienced a prolonged heat wave that spanned from California to Alaska, with water temperatures soaring to unprecedented levels. As a result, murres—resilient seabirds known for their deep diving and long-distance foraging—perished at unprecedented numbers. During this time, over 62,000 carcasses were found along coastlines, though researchers believe these represented only a fraction of the actual death toll, which revised estimates now place at four million.

The heat wave disrupted the marine food chain on multiple levels. Warmer waters reduced phytoplankton populations, depleting the fish stocks that murres depend on, such as herring and anchovies. At the same time, larger fish like salmon and Pacific cod required more energy in the warmer conditions, intensifying competition for already scarce prey. Starvation became inevitable for many murres.

The aftermath extended far beyond the immediate crisis. In the years following the blob, breeding colonies failed to produce chicks, severely hampering population recovery. Murres’ reliance on large colonies for protection from predators added to their vulnerability; with fewer birds, their nesting sites were increasingly exposed to threats.

Cascading Effects on Ecosystems

The catastrophic loss of murres is just one part of a broader ecological upheaval. Pacific cod stocks fell drastically, king salmon populations dwindled, and thousands of humpback whales likely died. Meanwhile, some species, like thick-billed murres, fared better due to more adaptable diets, highlighting the uneven impact of the heat wave on marine life.

For common murres, however, the outlook remains grim. Nearly a decade after the event, their numbers show no signs of recovery, suggesting potential permanent losses. This has profound implications for the marine food web, as murres play a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance.

While addressing the root cause—global warming—is paramount, Renner emphasized that localized conservation efforts can still make a difference.

Impact on British Columbia’s Marine Ecosystem

The 2014–2016 marine heatwave significantly impacted marine ecosystems along the Pacific coast, including BC. This prolonged period of elevated sea temperatures led to substantial ecological disruptions, notably affecting seabird populations and the broader marine food web.

In BC waters, the heatwave caused sea surface temperatures to rise markedly, with anomalies persisting into deep fjords. Research indicates that the surface marine heatwave commenced in early 2014, peaked at the start of 2015, exhibited a secondary peak in early 2016, and was gone by late 2016. However, subsurface temperature anomalies persisted between 2014 and 2018, indicating a lasting impact on the marine environment.

This thermal anomaly led to a decline in nutrient-rich cold waters, adversely affecting primary productivity. The resulting decrease in phytoplankton abundance had cascading effects throughout the food chain, impacting species dependent on these primary producers. Notably, there was also a significant die-off of the plankton-eating Cassin’s auklets from central California to British Columbia in the winter of 2014–2015, with an estimated death toll of around 250,000 to 500,000.

For more on this story, check out this article.