A newly born Bigg’s killer whale spotted off the coast of British Columbia carries a powerful legacy—one tied to the final chapter of orca captures in North America. According to the Pacific Whale Watch Association (PWWA), the calf is a direct descendant of Wake, an orca who was seized by SeaWorld in 1976 before being released due to public and legal pressure.

The calf was observed on March 20 in the eastern Juan de Fuca Strait, south of Victoria, swimming closely beside its mother. Identified as a 14-year-old orca named Sedna, the female is believed to be a first-time mother.

Photographs taken over the weekend show the calf with visible fetal folds and a bright orange tint, signs it was likely born just a week or two earlier. “These factors are normal and indicate the calf is quite young,” said Erin Gless, executive director of the PWWA.

The new addition brings cautious optimism to those monitoring marine mammals in the region, where threats to killer whales—especially the endangered southern residents—continue to mount.

Wake’s Story: Captivity and Return to the Wild

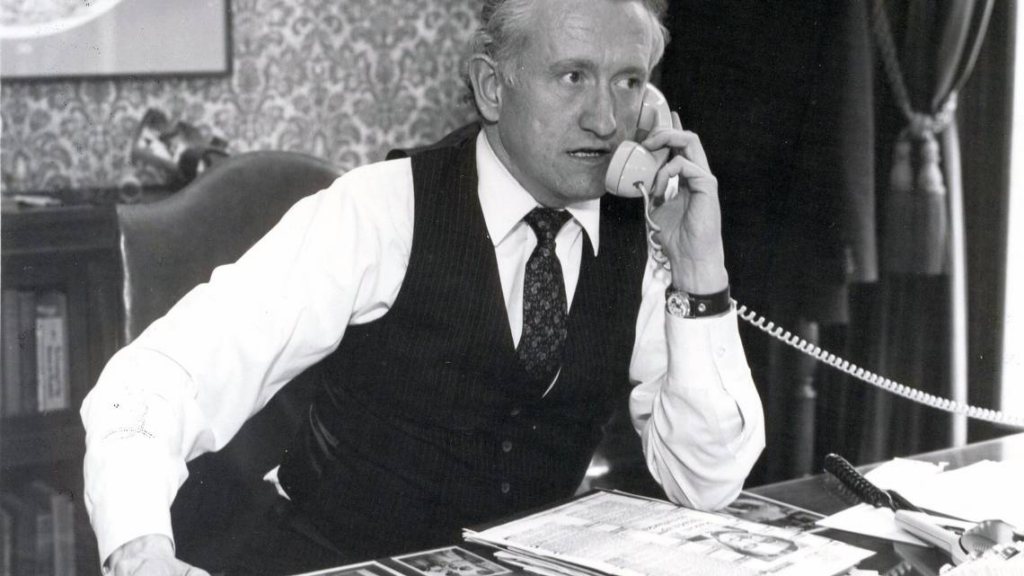

Sedna’s grandmother, Wake, was among six orcas taken by SeaWorld from Puget Sound in 1976. The event sparked outrage after Ralph Munro, then an aide to Washington Governor Dan Evans, witnessed the violent roundup while sailing. Disturbed by what he saw, Munro helped launch a lawsuit that ultimately forced SeaWorld to release the captured whales.

Wake, once freed, became a key figure in the wild population. She is thought to have given birth to eight calves, who then produced at least 16 more offspring—including Sedna.

The Legacy of Orca Captures in BC

The capture of wild orcas for display was common throughout the 1960s and ’70s, with British Columbia’s waters serving as one of the most targeted regions. Dozens of killer whales were forcibly removed from their pods and sold to aquariums around the world. The traumatic legacy of these captures still echoes today, with some family groups permanently disrupted.

Capturing orcas from the wild removed specific individuals from already small populations. In the case of the endangered Southern Residents, this significantly reduced the gene pool. A recent genetic study revealed that many of the remaining whales are closely related, with some showing signs of inbreeding depression—where reduced genetic diversity leads to lower fertility, poor health, and higher mortality among calves. This has contributed to a pregnancy failure rate of almiosst 70%.

For the Southern Residents, around 40% of the population was taken during the capture era, mostly young animals that would have been key to future reproduction. This severely limited their recovery.

The 1976 capture of Wake’s pod marked the end of this era, largely due to public backlash and the efforts of individuals like Munro. The same day a new calf was spotted, Munro’s death at age 81 was announced.

Bigg’s Orcas: Thriving, But Not Without Risks

Wake and her descendants belong to the population of Bigg’s killer whales—also known as transient orcas—which differ from the more well-known southern residents in both diet and behaviour. Bigg’s orcas hunt marine mammals, such as seals and sea lions, and have benefitted from the rebound of those prey populations over recent decades.

Researchers at Bay Cetology, based on Vancouver Island, estimate there are now close to 400 Bigg’s killer whales in the coastal BC region, including 140 calves born in the last 10 years. This stands in stark contrast to the roughly 73 endangered southern resident orcas remaining in the same waters.

While the Bigg’s population appears to be increasing, their future is not without challenges. All killer whales in BC face threats from underwater noise pollution, vessel traffic, toxic contaminants, and habitat degradation. These stressors interfere with communication, navigation, hunting, and overall health.

Southern residents are particularly vulnerable, struggling with inadequate food supply and high exposure to pollution.