The Salish Sea is far too noisy for its resident orcas to hunt efficiently and effectively, according to new research by the University of Washington and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The Salish Sea hosts two unique populations of orcas. Northern resident orcas only occasionally visit the Salish Sea, as they spend the majority of their time ranging from northern Vancouver Island to southern Alaska. Northern residents are considered threatened in BC, with a population of more than 300. Southern residents, however, spend the majority of their time in the Salish Sea. They are considered critically endangered, with a population of only 74.

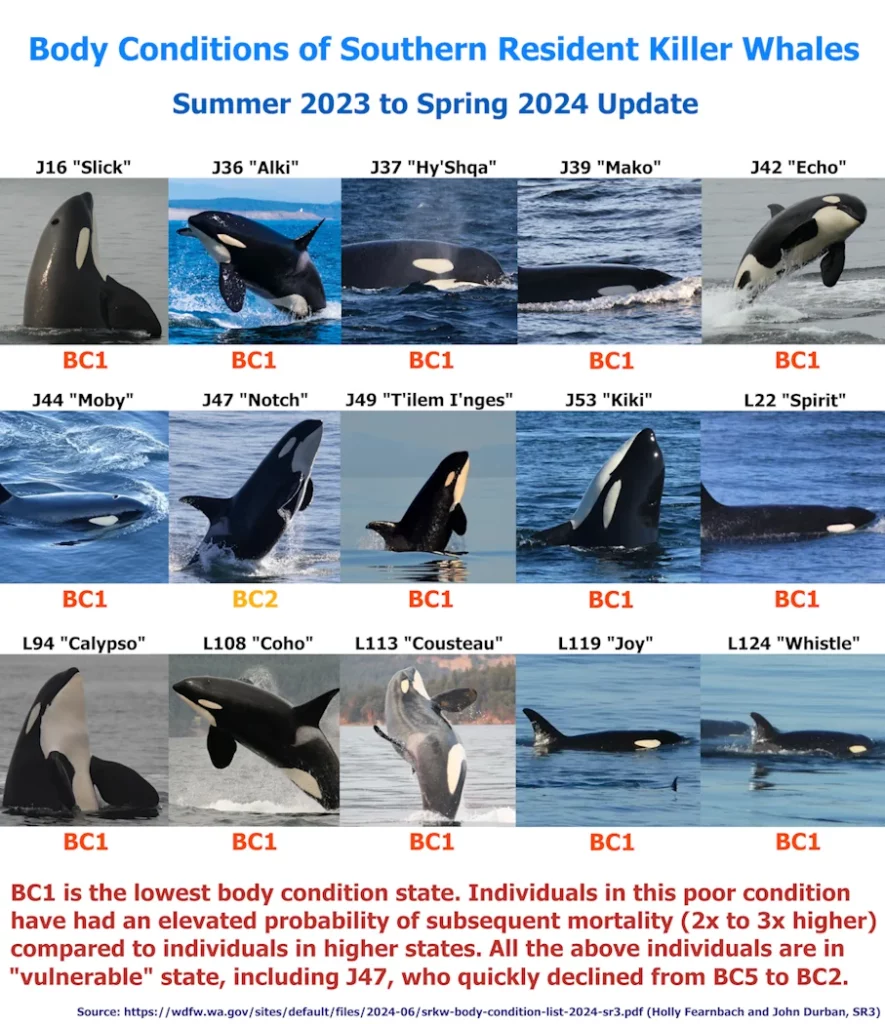

Southern resident killer whales have a diet heavily reliant on Chinook salmon. The depletion of wild Chinook salmon in BC has coincided with the decline of southern residents. In fact, there have been multiple sightings of emaciated southern resident killer whales in BC waters.

As part of the research, digital tags were temporarily attached to 25 individual whales to study how noise pollution from vessels affected three main killer whale hunting behaviours—searching (slow-click echolocation), pursuit (buzzes), and capture. The research found that “For every 1 dB increase in maximum noise level… there was a 12.5% decrease in the odds of prey capture by both sexes.” Females were especially affected, with a decrease of 58% in pursuing prey. The research team speculated that as the killer whales had to spend more time searching for prey in what would ultimately be an unsuccessful hunt, the females became reluctant to leave their babies at the surface where they would be in danger.

According to the paper, southern resident orca pods spend more time in parts of the Salish Sea with high ship traffic and, as such, are likely more heavily impacted.

“[This] shines a light on why southern residents in particular have not recovered. One factor hindering their recovery is availability and accessibility of their preferred prey: salmon. When you introduce noise, it makes it even harder to find and catch prey that is already hard to find,” said lead author Jennifer Tennessen

Northern and southern resident orcas use echolocation to find food. They send out short clicks that travel through the water and bounce off objects. These echoes return to the orcas with information about the type, size, and location of the prey. When they detect salmon, the orcas start a complex hunt involving more frequent clicking and deep dives to catch the fish.

The digital tags used in the study, also known as “Dtags,” are cellphone-sized and are attached noninvasively below an orca’s dorsal fin via suction cups. The tags collect data on the underwater sound levels at the whales’ locations, and also provide detailed information about the specific ways orcas hunt for prey.

Thanks to this technology, researchers were able to collect data on “deep dive” hunts as well. Out of six deep-dive hunts they studied, all of which occurred in particularly loud settings, only one such hunt was successful.

Initiatives such as the Echo Program by the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority aim to provide quieter waters for BC’s whales by encouraging vessels to slow down. However, Tennessen stresses that this is not the entire solution.

“When you factor in the complicated legacy we’ve created for the resident orcas — habitat destruction for salmon, water pollution, the risk of vessel collisions — adding in noise pollution just compounds a situation that is already dire,” said Tennessen. “The situation could be turned around, but only with great effort and coordination on our part.”

The paper was written in collaboration with scientists from other organizations, including Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the University of British Columbia, and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

For more on this story, check out this article.