Rockfish are a family of marine fish found in coastal waters of the North Pacific Ocean, including the Great Bear Sea. There are 38 different species of rockfish on the British Columbian coast, with some species living to 160 years old and growing up to 150 centimetres long. However, there are significant age and size differences between various rockfish species. Rockfish reach reproductive maturity between 3 to 25 years, depending on the species.

Habitat

Rockfish inhabit both shallow coastal waters as well as deep ocean habitats. They can live in depths over 500 meters. In rocky areas, they often hide under ledges or crevices during the day, coming out at night to feed on zooplankton and other small marine creatures. Many rockfish species are found around reefs, kelp forests, mudflats and estuaries, where they feed primarily on herring and other small fish, crabs, worms, and jellyfish. Many species of rockfish remain at the same site their entire adult lives.

Reproduction

Rockfish reach spawning maturity at the ages of 3 to 25, depending on the species. Rockfish are viviparous, meaning they give birth to live young after internal fertilization. Several months after fertilization, females give birth to thousands and even millions of tiny larvae. The survivors end up hiding in kelp, eelgrass, or rocks on the ocean floor. These tiny larvae eat small crustaceans, copepods, or fish eggs. As the juvenile fish grow and mature, they move to adult habitats in deeper water, with their diet now including herring, small fish, sand lance, and crustaceans.

The Importance of Rockfish for Great Bear Coast Communities

Rockfish are culturally significant to the Indigenous peoples of British Columbia’s coast, who have been harvesting rockfish for thousands of years. In particular, yelloweye rockfish and quillback rockfish are essential for traditional diets, providing protein, omega-3 fatty acids, essential vitamins, and year-round food security. For First Nations on the coast of British Columbia, resources such as rockfish are not only a food source but also cultural sustenance. Canada’s constitution grants Indigenous people priority access to fisheries for Food, Social and Ceremonial (FSC) purposes. However, exercising these rights has become increasingly difficult due to dwindling rockfish numbers. According to CCIRA’s Science Coordinator, Alejandro Frid, “the loss of traditional resources has a long history of affecting the physical, mental and spiritual well-being of Indigenous people throughout the world.” Before colonization, coastal First Nations’ stewardship ensured a thriving and sustainable food system without resource depletion. However, commercial and recreational fisheries have depleted traditional resources due to overfishing.

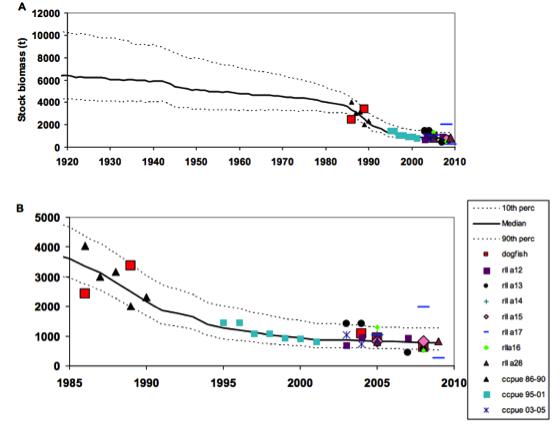

The Decline of Rockfish Numbers on the Great Bear Coast

Rockfish size and abundance have declined on the British Columbian coast, resulting in 16 species listed as species of concern. One of the leading causes of rockfish decline is overfishing. Rockfish are long-lived species that reproduce slowly, making them particularly vulnerable to overfishing. The overfishing of rockfish is particularly problematic as females start to reproduce once they mature. The average reproductive age for yelloweye rockfish is 34 years, while for quillback, reproductive maturity begins at around 11 years old. Therefore, the females must live a significant length of time before they can even reproduce. In addition, fecundity increases with age and size, which means the older the female rockfish, the more larvae it can produce. The larvae of older fish are also more robust and have augmented survival rates compared to the larvae of younger rockfish. Research has found that since the 1980s, the average size of yelloweye rockfish caught by Indigenous fishers on the Central Coast has declined by 45%, with the average size continuing to decrease yearly. Research has shown that the average yelloweye and quillback rockfish ages are 23 and 27.3 years, well below the maximum ages of 118 and 90, respectively. Moreover, a study across 282 sites found that old quillback and yelloweye rockfish are now rare. Put simply, rockfish are not living long enough, which means females are not reproducing enough.

Rockfish have been heavily targeted by commercial and recreational fishers, significantly reducing their numbers and average size. The fact that fisheries target larger fish has contributed dramatically to population declines, as this removes the most reproductive females from rockfish populations. In addition, rockfish end up being by-catch of bottom and mid-water trawling and the spot prawn trap fishery. This is particularly problematic for rockfish due to barotrauma, which results from “closed” rockfish swim bladders that do not adjust to rapid pressure changes during rapid ascent, causing them to expand with gasses. This results in their stomachs being pushed into their mouths. Recently, illegal rockfish poaching has been on the rise and has had a significant negative impact on conservation efforts.

Another major threat to rockfish is habitat destruction. Rockfish rely on complex and diverse habitats, such as rocky reefs and kelp forests, to survive. These habitats are being degraded or destroyed by human activities, such as bottom trawling, pollution, urbanization, and the removal of marine vegetation. This destruction has resulted in a loss of suitable habitat for rockfish and other marine life.

Climate change also poses a significant threat to rockfish populations. Rising ocean temperatures and acidification have already negatively impacted rockfish survival and reproduction. Ocean temperature and chemistry changes can alter the timing of spawning and juvenile fish survival.

Rockfish Conservation Areas

In the early 2000s, DFO realized that many rockfish species were on the verge of collapse. This resulted in the DFO creating the Rockfish Conservation Strategy, which established 164 rockfish conservation areas (RCAs) in British Columbia in 2007. To date, the RCAs have been moderately successful. Research on select RCAs found that yelloweye rockfish were, on average, 10.3 cm (21%) longer inside the RCAs than outside. As a result, First Nations are recommending expanding RCAs that house yelloweye rockfish. However, research also found that other rockfish species did not benefit from RCA protection. One reason for this may be illegal poaching, which means increased monitoring and enforcement are needed.

The Great Bear Sea Marine Protected Area Network

Presently, Coastal First Nations and the provincial and federal governments are planning a marine protected area (MPA) network for the Great Bear Coast. A critical element of the Great Bear Sea MPA Network is that it will include all existing RCAs. In addition, based on research undertaken for the Great Bear Sea MPA Network, some existing RCAs will be expanded, and many will have enhanced protection measures to ensure an increase in abundance and biomass, which is found in other well-managed and highly protected MPAs. A critical component of the Great Bear Sea MPA Network will be enhanced monitoring and enforcement by First Nations Guardians, which will reduce illegal poaching. Protecting rockfish is one of many reasons why the Great Bear Sea MPA Network must become a reality.