Among the distinguished creatures of BCs coastal waters, the sunflower sea star (Pycnopodia helianthoides) stands out as a true ocean giant. With as many as 20 flexible arms radiating from its central body, it’s one of the largest and fastest sea stars in the world, gliding with surprising ease along the seafloor.

Identifying the Sunflower Sea Star

True to its name, the sunflower sea star resembles the bright petals of a sunflower stretching out in all directions. Their colors range from deep purples and reds to golden yellows and oranges. Growing to more than a meter across, its sizable presence in tide pools and rocky reefs is unmistakable.

Unlike the more familiar, slower five-armed sea stars, sunflower sea stars utilize dozens of arms that propel them swiftly – sometimes reaching speeds up to 1 meter per minute – hunting prey with efficiency. Their diet consists mainly of sea urchins, clams, snails, and other slow-moving creatures scurrying across the ocean floor.

Keystone Role in Kelp Forests

The sunflower sea star is more than just a striking presence along the seafloor – it plays a keystone role in maintaining balance beneath the waves. By keeping sea urchin populations in check, sunflower sea stars prevent urchins from overgrazing kelp.

When urchins multiply unchecked, they can strip entire kelp forests down to bare rock, leaving behind so‑called “urchin barrens.” These losses are significant, as kelp forests provide food, habitat, and nursery grounds for many marine species.

Sara Ellison and the Sunflower Sea Star Crisis

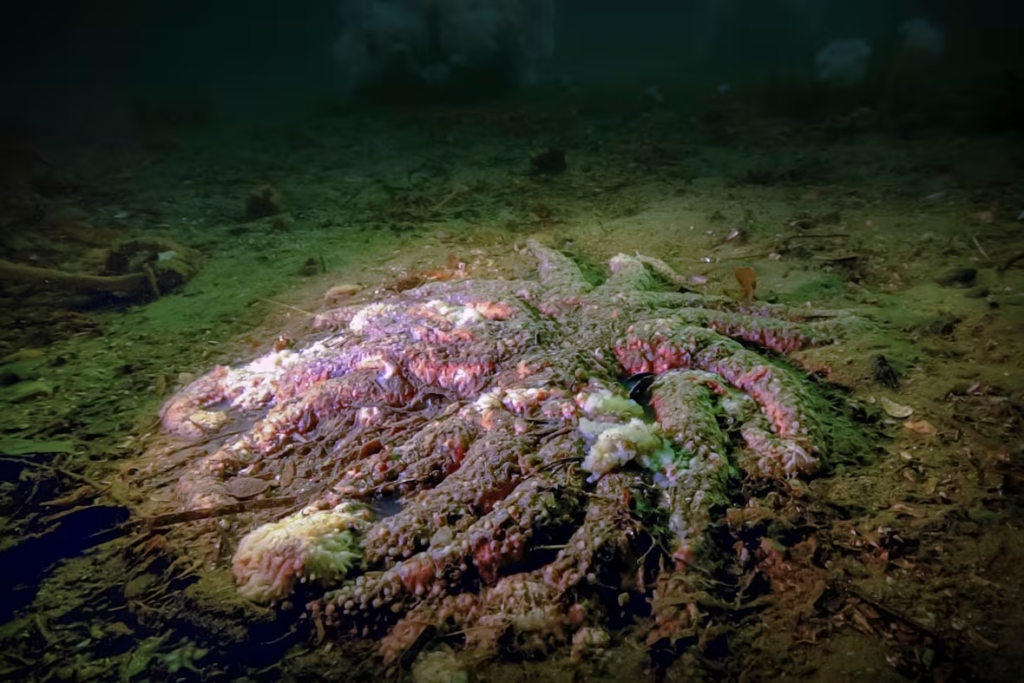

This sunflower sea star shows visible signs of the devastating wasting disease responsible for nearly six billion sea star deaths since 2013. Photo credit: Grant Callegari/Hakai Institute.

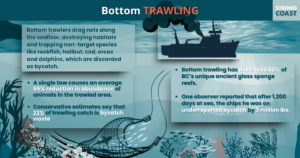

Marine naturalist Sara Ellison has closely observed sunflower sea stars amid one of the most challenging periods in their recent history. Since 2013, these sea stars have been devastated by Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD), a mysterious and lethal condition causing rapid tissue decay and disintegration. Studies report that populations have declined by as much as 94% across the Pacific Northwest.

Sara’s meticulous observations have helped reveal the extent of the disease’s impacts and contributed to research which recently identified the bacteria responsible, a major breakthrough. Ongoing research and conservation initiatives, informed by observations like Sara Ellison’s, include developing captive breeding programs aimed at restoring sunflower sea stars to their natural habitats.

Guardians of Coastal Habitats

Sunflower sea stars cling to survival in the cold, rugged fjords of British Columbia’s Central Coast, like Burke Channel. Photo credit: Grant Callegari/Hakai Institute and The Marine Detective

The dramatic decline of sunflower sea stars is a clear warning. Sara Ellison and fellow researchers stress that time is short. Without intervention, the loss of these sea stars could cause ripple effects felt for decades.

When sunflower sea stars disappear, sea urchins surge, and once‑lush kelp forests are stripped down to lifeless barrens. The loss spreads across the food web – fish lose nursery grounds, seabirds and mammals lose foraging areas, and coastal communities lose the protection and carbon storage that kelp forests provide.

Protecting and restoring sunflower sea stars shows why ocean conservation matters. From tackling diseases to protecting habitats, these efforts remind us that oceans are fragile and interconnected, where every species – from the many-armed sea star to the largest whale – matters.