Scientists and marine researchers are calling for stronger regulations on bottom trawling in the UK and Europe, citing its damaging impact on seafloor habitats—an effect increasingly likened to marine deforestation—with estimated annual costs of up to €11 billion due to environmental and economic losses.

The Impact of Bottom Trawling

Bottom trawling has long been under scrutiny due to its environmental effects and its negative impact on fish populations. Trawling can lead to overfishing by capturing both target and non-target species, including juveniles, at unsustainable rates.

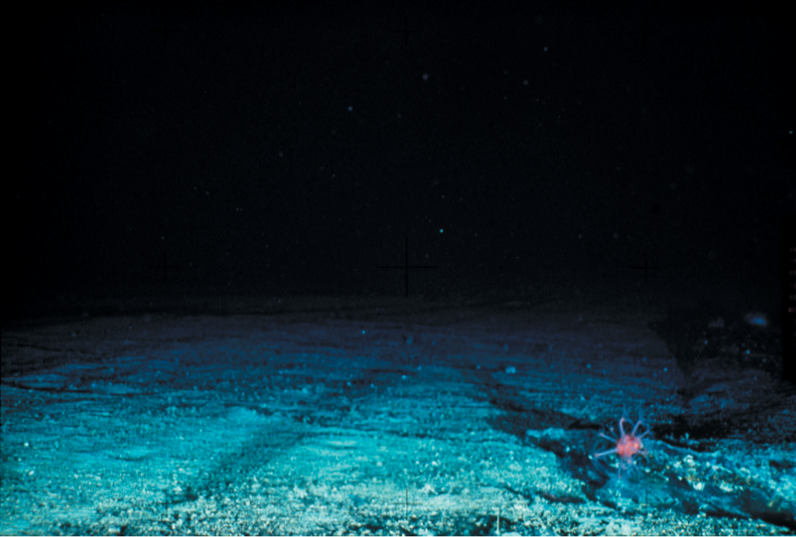

Marine scientists say bottom trawling can disturb vast areas of the seabed, destroying slow-growing species such as cold-water corals and sponges that serve as essential habitat for marine life. According to a 2021 study, bottom trawling disturbs around 4.9 million square kilometres of the ocean floor globally each year—an area roughly equivalent to the European Union.

These habitats, sometimes referred to as “marine animal forests,” are important for biodiversity, carbon storage, and the long-term health of fish stocks. The same 2021 study found that bottom trawling results in significant sediment disruption, releasing carbon previously locked into seabed sediments into the water column, potentially contributing to ocean acidification and global warming.

Despite marine protected areas (MPAs) being designed to conserve vulnerable habitats, many in Europe still allow trawling. Oceana, Seas at Risk, and other groups have joined to urge governments to restrict bottom trawling, especially in designated protected zones. They argue that continued trawling undermines conservation goals and long-term fisheries sustainability.

“Ending bottom trawling in Europe’s marine protected areas isn’t just good for the environment — it’s essential for saving billions in public costs.”

Enric Sala, National Geographic Explorer in Residence

“The science consistently shows that bottom trawling devastates these marine habitats. It of course devastates fish populations, undermines the very purpose of a marine protected area, and has a negative long-term impact on local fishers as well,” said Hugo Tagholm, executive director of Oceana UK.

Economic Costs and Public Subsidies

A recent analysis from National Geographic’s Pristine Seas programme estimates that bottom trawling results in a net economic cost of up to €11 billion annually across Europe, factoring in habitat loss, reduced fisheries productivity, and the impact on carbon stores. The study also notes that public subsidies play a role in sustaining the practice, particularly in countries like France and Spain.

“Ending bottom trawling in Europe’s marine protected areas isn’t just good for the environment — it’s essential for saving billions in public costs,” said Enric Sala, National Geographic Explorer in Residence, founder of Pristine Seas, and one of the authors of the study. “This move will save taxpayers money, protect marine life, boost the fishing industry and help us tackle global warming.”

The coalition of organisations—including Oceana, Bloom, and the Transform Bottom Trawling Coalition—is also advocating for a transition plan. Redirecting part of the estimated €1.3 billion in EU fisheries subsidies, they argue, could help fishing communities adopt less damaging practices while maintaining livelihoods.

“With the UN Ocean Conference fast approaching, world leaders have an important choice to make: uphold their commitments to protect our ocean or allow the continued destruction of our marine protected areas. To me, and everyone that cares about our blue planet, the choice is clear,” said Alexandra Cousteau, president of Oceans 2050.

Expanding Scientific Evidence

Extensive scientific research over the past decade has documented the ecological impact of bottom trawling. Another 2021 study found that bottom trawling not only physically damages seafloor habitats but also releases large amounts of carbon stored in marine sediments—estimated at up to 1.5 billion tonnes of CO₂ emissions per year. This is roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of the aviation industry.

Another study, published in Frontiers in Marine Science in 2023, concluded that repeated trawling reduces the number and variety of animals that live on the seafloor, disrupts the food chains they’re part of, and changes how nutrients move through the ecosystem in ways that can take decades to recover—if they recover at all.

Implications for British Columbia

The Pacific groundfish trawl fishery is active off BC, and while there are habitat protection measures in place—including some closures around sensitive sponge and coral areas—concerns remain. A 2017 study found that repeated bottom trawling off the BC coast had significantly changed the mix of animals living on the seafloor and led to a noticeable drop in the amount of non-target marine life caught or affected by trawling.

Additionally, BC is home to rare and ancient glass sponge reefs, some of which are thousands of years old and uniquely vulnerable to bottom contact fishing. Scientists estimate that 50% of these reefs were destroyed by bottom trawlers before their existence was even discovered, highlighting their fragility and the urgency of protection efforts. Although several reefs have been protected through fisheries closures, experts continue to call for broader no-trawl zones to prevent irreversible damage. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) has acknowledged the ecological significance of these reefs, which are found nowhere else in the world in such abundance, and designated 2,410 square kilometres of sponge reef habitat as protected in 2017.