British Columbia is renowned for its mesmerizing landscape, biodiversity, and wildlife. The Douglas Channel, nestled in the central coast of BC, is one of the most unique and diverse ecosystems of the province. From lush forests to rugged mountains to waters teeming with life, the Douglas Channel presents a rare sight for anyone who values nature and its tranquil beauty.

The region is also known for its abundant marine life, such as humpback whales, killer whales, dolphins, seals, and sea lions, making it a hub for eco-tourism and research purposes. Unfortunately, the Douglas Channel is under threats from various human activities, and a comprehensive solution is needed to protect this valuable natural resource.

History of the Douglas Channel

Without counting smaller side-inlets, the total waterway length of the fjord dominated by Douglas Channel is around 320 km, which makes it longer than Norway’s Sognefjord (203 km) and rivalling Greenland’s Scoresby Sound at 350 km.

The Douglas Channel has been home to Indigenous communities for thousands of years, and it holds great cultural and spiritual significance for them. The Indigenous communities that live there include the Gitga’at, Kitasoo/Xai’xais, Haisla, and Gitxaala Nations. They have been instrumental in advocating for the protection of species, traditional hunting practices, and the sustainable use of marine resources. As a result, the region has seen an increase in tourism centred around cultural practices and Indigenous heritage, supporting local economies and conserving the area’s cultural integrity.

Aside from Indigenous communities, there are also various non-Indigenous settlements along the coast that heavily rely on the Douglas Channel for their livelihoods. These include fishing villages, logging towns, and tourism-based communities. The natural resources found in the region provide employment opportunities and support local economies. The well-being and sustainability of these coastal communities are intricately tied to the health of the Douglas Channel.

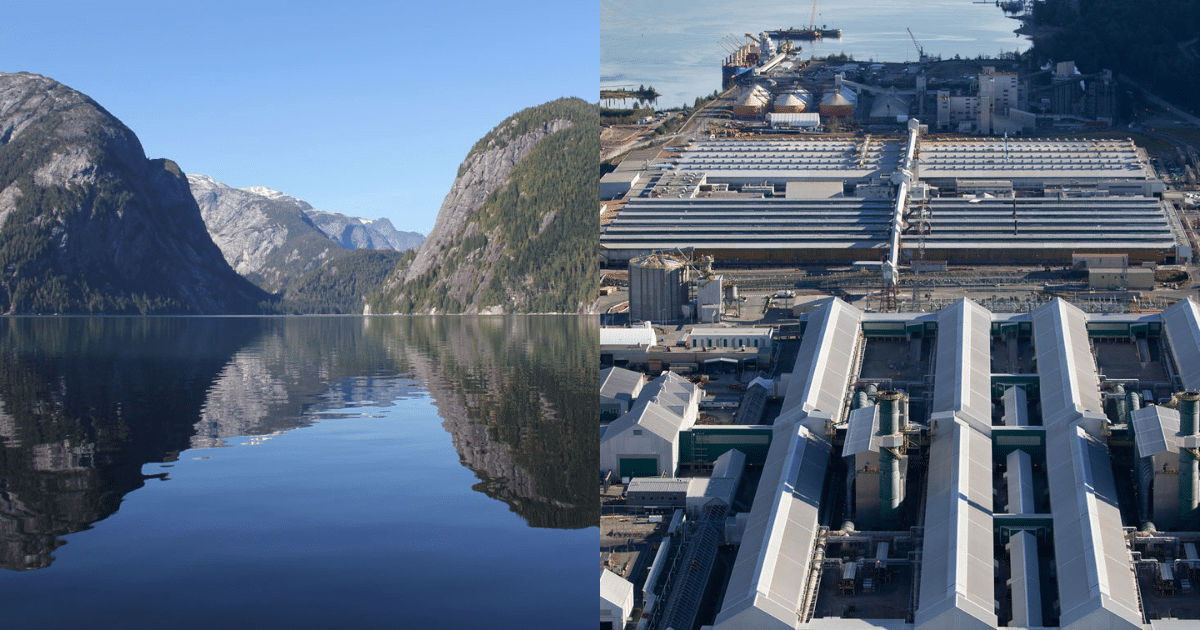

However, industrialization has led to increased ship traffic, threatening the waters and delicate ecosystem of the Douglas Channel. The region has also been a focus for LNG development, further intensifying concerns about its protection.

The Magnificent Fauna of the Douglas Channel

The Douglas Channel is home to a diversity of unique species, making it an essential habitat for the biodiversity of British Columbia. The region provides critical feeding and breeding grounds for various marine mammals, fish, and birds.

Some of the marine animals found in the Douglas Channel include humpback whales, killer whales, Pacific white-sided dolphins, Dall’s porpoises, Steller sea lions, and harbour seals. The region is also home to a diverse range of seabirds, such as bald eagles, tufted puffins, and marbled murrelets.

In recent years, the Channel has witnessed a dramatic recovery in pods. One study found that the humpback whale population in this region doubled from 67 in 2004 to 137 in 2011. Latest estimates from BC Whales in 2019 put the number of individual humpbacks identified in the Caamano Sound to Douglas Channel region at 426. One key factor that has contributed to this is government regulation on whaling that started in 1966. But it’s not the only reason. Researchers postulate that krill and juvenile herring are schooling in the upper Douglas Channel, attracting more whales.

Nevertheless, several species found in the Douglas Channel are still listed as endangered, threatened, or of special concern, including the southern resident killer whales and humpback whales. While the whale population has grown, the risks they face are also increasing. Whaling may have stopped, but other human activities, such as pollution, overfishing, and disturbance from vessels are on the rise. Protecting the Douglas Channel is vital for the protection of these species and for maintaining a healthy marine ecosystem.

Flora of the Douglas Channel

The Douglas Channel is not only home to magnificent fauna but also boasts a diverse array of flora. The region’s temperate rainforest is characterized by towering trees, such as western red cedar, sitka spruce, and western hemlock. These old-growth forests provide important habitat for wildlife and play a crucial role in mitigating climate change. The region also includes intertidal and subtidal habitats, which support a variety of marine plant life, including kelp forests and eelgrass beds.

In addition to providing food and shelter for wildlife, the flora of the Douglas Channel is culturally significant to Indigenous communities. Many plants are used for traditional medicine, weaving, and spiritual ceremonies. Protecting these diverse plant species is crucial for preserving Indigenous cultural practices and maintaining the region’s ecological balance.

Potential Threats to the Douglas Channel

Despite the cultural and ecological significance of the Douglas Channel, there has been a rise in activities potentially harmful to the region’s ecosystem. The construction of liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals, pipelines, and other industrial activities poses significant threats to the area’s biodiversity and marine life. These activities can lead to spills, noise pollution, habitat modification, and interruptions of migratory pathways which can cause negative impacts on the region’s natural resources. The impacts can be far-reaching, from affecting the ecosystem to communities that rely on these resources for their livelihoods.

However, the most pressing threat is the increase of ship traffic. A recent study published in Endangered Species Research highlights the alarming impact of increased shipping traffic related to the LNG export terminal in Kitimat. This $38 billion project, set to open in 2025, will escalate shipping in the lower Kitimat Fjord System, dramatically increasing the risk of fatal collisions between ships and the recovering populations of fin and humpback whales.

The study forecasts a potential thirtyfold increase in whale fatalities by 2030. These estimates were informed by data that was collected by the SWAG (Ships, Whales, & Acoustics in Gitga’at Territory) Project, which was collaboratively developed by the Gitga’at Nation, North Coast Cetacean Society, and WWF Canada. The potential number of deaths due to ship strikes could rise to two fin whales and 18 humpback whales annually, a stark contrast to the current rates. This increase could reverse the recent recovery of these species, which are listed as “Threatened” and “Special Concern” under Canada’s Species At Risk Act.

In addition to the impending threat from LNG-related shipping, the area has already witnessed a high number of whale strikes. Recent incidents involving various vessels have highlighted the vulnerability of these marine giants, particularly humpbacks, which lack the biosonar capabilities of orcas and are often unaware of nearby ships.

The study advocates for immediate action to mitigate these risks. Proposed measures include seasonal restrictions on shipping during peak whale months and the implementation of slowdown zones to reduce vessel speeds, which could significantly decrease fatal whale strikes. The project is also expected to contribute significantly to carbon emissions, further intensifying environmental concerns.

Another threat to whale populations is noise pollution, which can significantly disrupt their communication, behaviour, and health. It interferes with their vital acoustic signals, leading to communication breakdowns and altered social interactions. Chronic noise exposure induces stress, potentially causing behavioural changes like altered feeding and migration patterns, and can even lead to hearing loss. Additionally, noise pollution impacts prey species, further challenging whale survival.

Without effective and prompt intervention, the study warns of “unsustainable losses” to the fragile recovery of these magnificent creatures. The call for action is clear: it is crucial for industry and communities to heed these warnings and implement protective measures to safeguard the delicate balance of life in the Douglas Channel.

Defending the Douglas Channel

Active involvement of Indigenous communities, environmental groups, and policy-makers is necessary to ensure the region’s biodiversity and cultural values are preserved. There’s a need for the establishment of marine protected areas, proper monitoring, and surveillance of activities that threaten the region’s integrity.

The Douglas Channel presents a rare and valuable natural resource that requires sustainable protection. The region’s biodiversity and cultural heritage embody the essence of British Columbia and play an important role in the province’s economy. Through innovation, collaboration, and sustainability, we can achieve a healthy and resilient Douglas Channel that can continue to be a thriving economic engine for current and future generations. Establishing the Great Bear Sea Marine Protected Area Network is an important component of making this happen.