Few animals inspire as much awe and intrigue as the giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini). This colossal cephalopod is a master of disguise and an amazingly intelligent invertebrate. For those living along the coast, the octopus is a reminder of just how much life and intelligence exists just beneath the surface.

A True Giant: Identification and Awe-Inspiring Biology

The giant Pacific octopus rightfully earns its name. It is the largest octopus species on Earth, with an arm span that can reach a staggering nine metres (30 feet) across, though individuals with a four- to six-meter (13-20 feet) span are more commonly encountered. Weights can exceed 45 kilograms (100 pounds), with some unconfirmed reports suggesting much larger individuals. Their lifespan typically ranges from three to five years, a relatively short period for such a large and complex animal.

One of the giant Pacific octopus’ most remarkable features is its ability to change colour and texture in a fraction of a second. Their skin contains thousands of specialized pigment sacs called chromatophores, which are surrounded by tiny muscles. By contracting or expanding these muscles, the octopus can flash an astonishing array of colours, from deep reds and browns to mottled whites and yellows. They can also alter their skin texture to mimic rocks or seaweed, further enhancing their camouflage. This incredible skill is controlled by their sophisticated nervous system and keen eyesight.

Their body is soft and boneless, allowing them to squeeze through incredibly small openings. The beak, located at the centre of its eight powerful arms, is the only hard part of its body and resembles that of a parrot. Each arm is lined with two rows of suckers, each sucker independently controlled and equipped with chemoreceptors, allowing the octopus to “taste” what it touches. A giant Pacific octopus can have over 2,000 suckers in total, providing immense gripping power and sensory information.

The giant Pacific octopus possesses three hearts. Two pump blood through the gills and one circulates it to the rest of the body. Their blood is blue, due to a copper-rich protein called hemocyanin, which is more efficient at transporting oxygen in cold, low-oxygen environments.

All octopuses possess a large brain-to-body mass ratio and demonstrate impressive problem-solving abilities, learning capabilities, and even playful behaviour. They can navigate mazes, open jars to obtain food, and have been observed using tools in rudimentary ways. Each arm has a degree of independent control, managed by a complex nervous system, allowing for sophisticated manipulation and coordination.

Habitat and Distribution: Finding the Giant Pacific Octopus along BC’s Coast

The giant Pacific octopus is found throughout the coastal North Pacific Ocean, from California to British Columbia and Alaska, across the Aleutian Islands, and down to Japan. Along the BC coast, they are a common resident, thriving in the cool, oxygen-rich waters. They can be found from the intertidal zone down to depths of at least 100 meters (330 feet), and occasionally much deeper.

Giant Pacific octopuses are typically solitary creatures and prefer to occupy dens like small caves, crevices in rocky reefs, or spaces under boulders. They are territorial and will often stay in a favoured den for extended periods, sometimes weeks or months, especially if food is plentiful nearby.

A Master Hunter: The Giant Pacific Octopus’s Role in the Marine Food Web

The giant Pacific octopus is an intelligent and highly effective predator, occupying a significant position near the top of the invertebrate food web on BC’s coast. Their diet is varied and depends on what is available in their local habitat. They are known to prey on a wide range of animals, including:

- Crustaceans: Crabs (such as Dungeness and rock crabs) are a particular favourite, along with shrimp and lobsters.

- Molluscs: Clams, scallops, abalone, and other snails are also common prey. They can use their powerful arms and suckers to pull open bivalve shells, or drill a hole through the shell with their radula (a toothed, tongue-like organ) and inject a paralyzing, flesh-dissolving saliva.

- Fish: Small fish, including rockfish and sculpins, can be ambushed and captured.

Their hunting strategies are diverse. They might actively forage, using their arms to explore crevices and pry open shells, or they may employ an ambush technique, relying on their exceptional camouflage to lie in wait for unsuspecting prey to wander too close. Once prey is secured, it is pulled towards the powerful beak and consumed.

While a formidable predator itself, the giant Pacific octopus is not without its own threats. Larger individuals have few natural predators, but juveniles can fall prey to lingcod, rockfish, harbour seals, and sea lions. Very large giant Pacific octopuses may occasionally be targeted by larger sharks or even particularly ambitious marine mammals. Their primary defence mechanisms are their incredible camouflage, their ability to release a cloud of ink to confuse attackers, and their speed and agility in jetting away by expelling water through a siphon.

Reproduction: A Final Act of Devotion

The reproductive cycle of the giant Pacific octopus is a poignant story of dedication. Mating can be a cautious affair, as males risk being cannibalized by larger females. The male uses a specialized arm, the hectocotylus, to transfer spermatophores (packets of sperm) into the female’s mantle cavity.

After mating, the female giant Pacific octopus finds a secluded, protected den, often in deeper water. Here, she will lay thousands of tiny, rice-grain-sized eggs, which she weaves into long, braided strings and attaches to the roof of the den. This process can take weeks. For the next six to seven months (or longer, depending on water temperature), the female dedicates herself entirely to her brood. She constantly cleans the eggs, aerates them by gently blowing currents of water over them with her siphon, and protects them from predators. Tragically, during this entire period, she does not eat. This leads to her death soon after the eggs hatch.

The tiny hatchlings drift in the water column as part of the zooplankton for several weeks or months before settling on the seabed to begin their relatively short, but extraordinary, lives.

Threats to the Gentle Giants of BC

Despite their adaptability, giant Pacific octopuses face a number of threats in British Columbia’s waters, many stemming from human activities:

- Habitat Degradation and Loss: Coastal development, pollution from industrial and urban runoff, and physical disturbances to the seabed (such as dredging or bottom trawling) can damage or destroy the rocky reefs, kelp forests, and den sites that giant Pacific octopuses rely on.

- Pollution: Chemical pollutants, including heavy metals, pesticides, and persistent organic pollutants (POPs), can accumulate in marine sediments and in the octopus’ prey. As predators, octopuses can bioaccumulate these toxins, which may affect their health, reproductive success, and longevity.

- Overfishing and Bycatch: While there isn’t a large-scale targeted commercial fishery for giant Pacific octopuses in BC, overfishing of their prey species, such as crabs and certain fish like rockfish, sole, flounder, and lingcod, reduces their food availability and impacts their populations. In addition, octopuses can also be caught as bycatch.

- Global Warming: Rising sea temperatures can affect the distribution and abundance of the giant Pacific octopus’s prey species. Warmer waters may also increase the prevalence of certain diseases. Increased acidity due to the absorption of atmospheric CO2 can negatively affect calcifying organisms like crabs, clams, and scallops, which are key components of the octopus’ diet.

The Indispensable Role of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

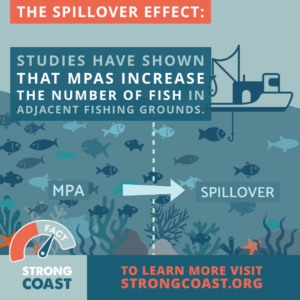

The protection of the giant Pacific octopus and the rich marine ecosystems they inhabit can be supported by well-managed Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). MPAs offer numerous benefits, including:

- Sanctuary for Growth and Reproduction: MPAs can provide safe havens where giant Pacific octopuses can find secure dens, forage undisturbed, and reproduce successfully. Protecting egg-brooding sites is particularly crucial.

- Preservation of Habitat and Biodiversity: By restricting harmful activities, MPAs safeguard the complex habitats that GPOs and their diverse prey species depend on. This helps maintain the overall health and sustainability of the coastal food web.

- Educational and Sustainable Tourism Opportunities: MPAs can foster a greater appreciation for marine life, like the giant Pacific octopus, promoting responsible tourism and educating the public about the importance of marine conservation.

The giant Pacific octopus is more than just a large cephalopod; it is a symbol of the wild beauty and ecological complexity of British Columbia’s coastal waters. Its intelligence, incredible adaptability, and vital role as a predator underscore its importance.