Introduction: The Herring Roe Fishery

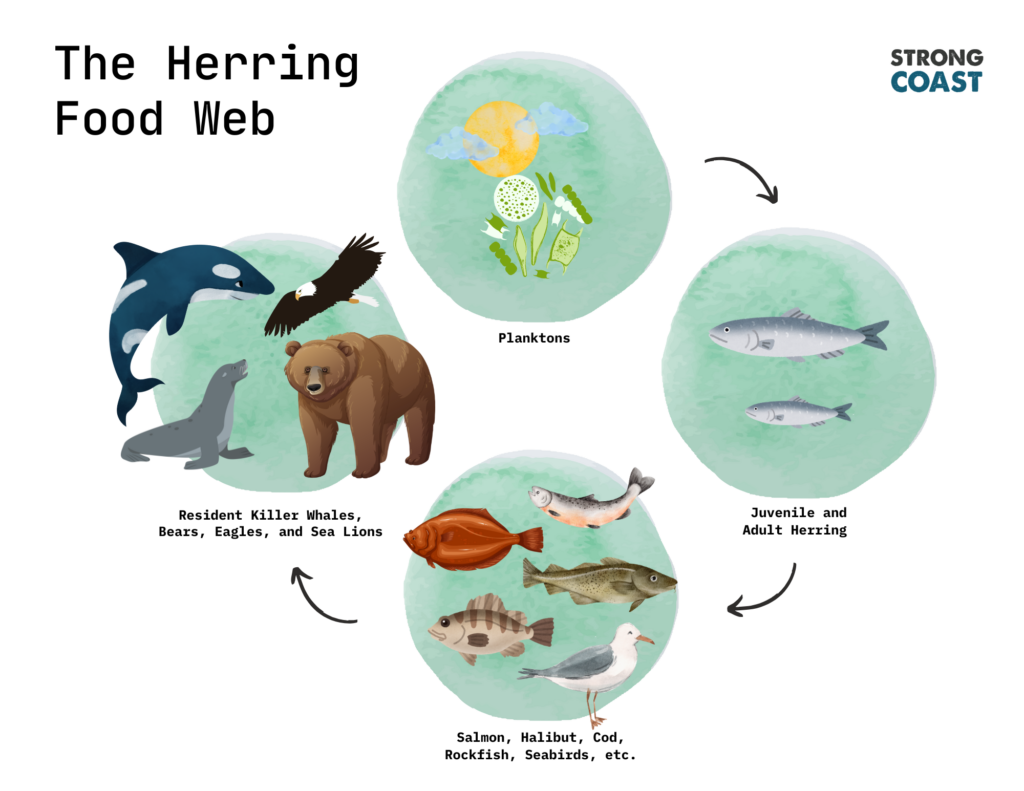

Pacific herring are a keystone species in British Columbia’s marine food web, serving as a crucial food source for a variety of fish, including Chinook, coho, sockeye, halibut, lingcod, and different rockfish species; marine mammals, such as humpback whales, orcas, sea lions, and seals; and seabirds, including common murres, rhinoceros auklets, marbled murrelets, and bald eagles. Despite their ecological significance, Pacific herring are commercially harvested in BC, primarily for their roe. The herring roe kill fishery targets mature, egg-bearing female herring to extract their roe (eggs), which is exported to Japan as a delicacy known as kazunoko. This fishery is viewed as wasteful because both the males and females are killed just for the roe, with their bodies being used for fertilizer and fishmeal.

Understanding the Herring Spawn

Herring gather in large schools in shallow waters or estuaries during their spawning period, with a single spawning event stretching over many kilometres of shoreline. In British Columbia, 18 percent of our coast has been classified as herring spawning habitat, although spawning sites have been disappearing from our coast for decades. Pacific herring exhibit strong spawning site fidelity, meaning they typically return to the same spawning grounds yearly. This behaviour is a common trait among many fish species and is crucial for the survival and maintenance of distinct herring populations. Site fidelity in spawning helps ensure that herring spawn in locations with environmental conditions suitable for the survival of their eggs and larvae. Research has found that the homing behaviour of Pacific herring is driven by a combination of environmental cues, such as water temperature, salinity, and possibly even magnetic fields, in addition to learned social behaviours.

Females lay their sticky eggs on seaweed, sea grass, or rocks, which are then fertilized by the milt (sperm) male herring release into the water. The milt turns the water in the spawning ground into a distinctive chalky white, as seen in the image below. Egg adhesion is vital for protecting them from being washed away or eaten by predators, although many are consumed by both land and marine species. The eggs incubate for about 10 days to a few weeks, depending on the water temperature. During this time, they develop into larvae while still attached to the substrate.

A single mature female Pacific herring can spawn 20,000 eggs annually, averaging between 6 to 8 spawns in her lifetime. This means a female herring has the potential to spawn close to 200,000 eggs. One of the many criticisms of the herring sac roe kill fishery is that it removes reproductive females from herring populations.

After hatching, juvenile herring feed mainly on zooplankton until they reach maturity at two years of age. This is why herring are a keystone species; they turn the ocean’s plankton into energy that literally fuels the entire marine food chain. Mature herring migrate to deeper water, feeding on various organisms such as crustaceans, mollusks, worms and other small fish.

BC’s Herring Roe Kill Fishery and Shifting Baselines

One significant issue with the herring sac roe kill fishery is that it falls victim to shifting baselines. According to Daniel Pauly, shifting baselines is when each generation perceives environmental conditions based on their own limited experience rather than historical conditions. Over time, as ecosystems degrade gradually, people adjust their expectations to the new, often diminished state, leading to a normalization of environmental decline. In the case of the DFO and its management of herring, the baseline that is used is from the 1950s. However, by this time, herring populations had already declined drastically due to 60 years of aggressive herring fishing, which had government officials ringing the alarm bells in 1910. To put this into perspective, in 1962, the BC catch peaked at 237,600 tons, which is nearly three times the entire spawning biomass of herring in the SOG today.

BC’s Herring Roe Kill Fishery

The herring roe kill fishery in BC is divided into several designated fishing areas, each with its own management regulations and harvest quotas. Many of these areas have experienced closures recently due to a long history of overfishing and mismanagement. The herring sac roe fishery actually includes four different fisheries, each with its own quota. These fisheries are the special use, food and bait, seine, and gillnet fisheries. Each of these fisheries has its own quota and a different number of allotted licenses. For instance, for the 2023/2024 season, the Strait of Georgia had 249 licensed seine vessels and 1,185 licensed gillnet vessels engaged in harvesting. The numbers below refer to the seine and gillnet fisheries only.

1. Strait of Georgia (SOG) (Area 17 & 18): Historically, it is the most productive region, centred around the east coast of Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands. Unlike other areas, the Strait of Georgia has experienced no closures in recent years. Between 2010 and 2019, harvest rates were fixed at 20 percent of the estimated spawning biomass, meaning that total allowable catch (TAC) fluctuated between 8.5 and 26 thousand metric tonnes. For example, the TAC for 2015/2016 for seine and gillnet fisheries combined was 19,697 metric tonnes. However, for some of these years, the spawning mass was significantly overestimated. For instance, for the 2018/2019 fishery, the TAC for the kill fishery was 21,000 metric tonnes, which was based on a 122,000 metric tonne spawning biomass return (the total weight of the fish in a stock that are old enough to spawn). However, the actual return was only 85,700 tonnes, resulting in significant overfishing at a harvest rate of 25 percent. Despite this miscalculation, the harvest rate for the 2019/2020 fishery, which had a TAC of 11,944 tonnes across all fisheries, was not reduced. Instead, it remained at 20 percent of the estimated spawning biomass. The TAC for the seine and gillnet fisheries was 9240 tonnes. For the 2020/2021 season, a 20 percent harvest rate resulted in a TAC of 7,850 tonnes for the seine and gillnet fisheries. The 2021/2022 season was disastrous despite the harvest rate being reduced to 10 percent. The TAC for the seine and gillnet fisheries was set at 7621 tonnes. However, only 4,473 tonnes were harvested. This means that the DOF greatly overestimated the returning spawning biomass.

For the 2022/2023 season, the TAC was set at 6,625 tonnes for all fisheries despite a 20 percent decrease in spawning biomass between 2020 and 2022. At the time, many scientists argued that this TAC was at a minimum 18 percent of the return. As with the previous year, TAC was not met, with only 50% of the allowable catch being landed. Despite the inability of the herring fishery kill fleet to meet TAC the previous two seasons, and despite the fact that the SOG herring spawning biomass declined by 26%, falling from 129,500 tonnes to 85,700 tonnes, 2023/2024 TAC was increased to 6281.9 tonnes for the herring and seine fisheries. The increase of the 2024-2025 TAC for the SOG to 9750 tonnes, based on a 14 percent harvest rate, has been met with significant criticism, with organizations like Pacific Wild and WSÁNEĆ hereditary chiefs calling for a moratorium. In asking for a moratorium Tsawout Hereditary Chief Eric Pelkey (WIĆKINEM) said, “We are deeply frustrated. How can DFO justify increasing herring harvests while stocks are in steep decline in our territories?” WSÁNEĆ hereditary chiefs also called for a moratorium in November 2019.

Criticism of SOG openings also extends to others. For instance, marine industry professionals like Colin Griffinson, a captain at Pacific Yellowfin Luxury Adventure Charters, are concerned about the overfishing of herring.

“I have witnessed the collapse of herring in the North Atlantic, and the result will be the same in BC, unless Canada does more to protect these fragile stocks. As a marine tourism operator, my livelihood and that of countless others directly depends on the health of herring,” he said.

2. Central Coast (Area 6 & 7): Includes Bella Bella and nearby waters, where herring spawn in significant numbers. The Central Coast sac roe kill fishery has experienced significant closures over the last 15 years, with the only openings being in 2014/2015, 2015/2016, and 2016/2017, with the TAC being 690, 626, and 213 tonnes, respectively.

3. Haida Gwaii (Area 2W & 2E): Once a major spawning ground, now severely depleted due to overfishing. The extreme overfishing in this area has resulted in this kill roe fishery being closed since 2002.

4. Prince Rupert District (Area 4 & 5): A key area for Indigenous and commercial fisheries. The Prince Rupert District was open for the herring roe kill fishery for most of the 2000s and 2010s, with the catch ranging from 1,000 to 4,500 tonnes. However, in 2018, only 416 of the 2048-tonne TAC was caught. This resulted in the fishery being closed from 2019/2020 to 2021/2022. In 2022/2023, the roe kill fishery was reopened with a TAC of 186 tonnes. For the 2024/2025 season, the herring roe kill fishery TAC has been increased to 929 tonnes.

5. West Coast of Vancouver Island (Area 23 & 24): Subject to fluctuating herring populations, with occasional fishery closures due to low stock levels. This fishery was closed in 2005/2006, only to be reopened for the 2015/2016 season, which had a failed harvest. The fishery has been closed ever since.

Industry Opposition

In response to the 2024 moratorium request by the WSÁNEĆ hereditary chiefs , the BC Seafood Alliance and other commercial fishing spokespeople said herring numbers only look low, because the fish move around and spawn in different places.

However, Tsawout Hereditary Chief Eric Pelkey (WIĆKINEM) disputed this: “The notion that the herring just migrate all around the territories is really misguided… [Herring] come back to the same place. They come back in groups, and they’re like families,” referring to the idea of spawning site fidelity.

He also disagreed with the argument that the quota can be increased because herring populations have been recovering in recent years. While his community does see juveniles, or fingerlings, trying to establish in the area, “the problem is, as soon as those fingerlings grow up to be really healthy adult herring, they open it up commercially again and clean them right out again.”

Why Herring is Vital to BC’s Coastal Economy and Ecosystems

Numerous studies have shown that herring is a keystone species, meaning its decline directly impacts the entire marine food web. It is a primary food source for Chinook salmon, which in turn are essential for endangered southern resident orcas, sea lions, Pacific white-sided dolphins, halibut and various sea birds to name a few. Other fish and mammals that depend on herring include humpback whales, Pacific white-sided dolphins, sea lions, Chinook, coho, sockeye, halibut, lingcod, rockfish, dogfish, common murres, rhinoceros auklets, puffins, marbled murrelets, gulls, terns, cormorants, and bald eagles.

Beyond its immensely important role of sustaining the marine food web, herring is also an economic engine for British Columbia’s marine tourism sector. The $1.2 billion marine-based tourism industry, which includes fishing lodges, wildlife charters, and whale watching, is dependent on thriving marine food web, with herring at its foundation.

Conclusion: Protecting Herring Through the Great Bear Sea Marine Protected Area Network

The continued decline of Pacific herring populations, especially in the Strait of Georgia and across BC’s coastal waters, is not merely a symptom of mismanagement—it is a warning. Industrial roe kill fisheries, driven by outdated baselines and unsustainable harvest rates, remove vast numbers of mature, egg-bearing females from the food web, undercutting herring reproduction at its source. This practice, deeply criticized by Indigenous leaders, marine scientists, and coastal stakeholders alike, not only threatens the herring themselves but weakens the entire marine food web they sustain—from salmon to whales to seabirds—and jeopardizes the coastal economies that depend on them.

To reverse this trend, a shift in marine governance is essential—one that prioritizes ecological resilience and long-term sustainability over short-term exploitation. The proposed Great Bear Sea Marine Protected Area (MPA) Network represents a vital opportunity to realize this shift. Encompassing one of the most biodiverse regions of Canada’s Pacific coast, the MPA offers a framework through which herring spawning grounds can be safeguarded, fishing pressure reduced, and traditional Indigenous stewardship practices—like the sustainable roe-on-kelp harvest—restored and supported.

By integrating herring conservation into the management priorities of the Great Bear Sea MPA, the ecological integrity of entire marine ecosystems can be preserved. In doing so, we not only protect a keystone species but also lay the groundwork for the return of a viable, sustainable community-based herring fishery—one that can coexist with Indigenous rights, marine biodiversity, and coastal livelihoods. Let this be the turning point where conservation and collaboration replace collapse.