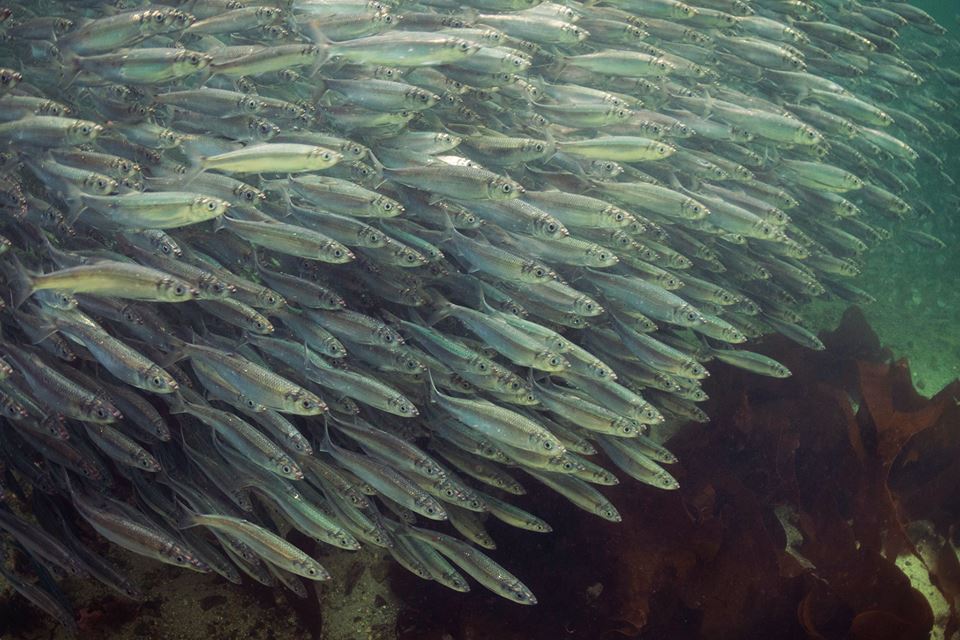

The Pacific herring may be the single most important species on our coast. Herring are small forage fish up to thirty centimetres long and 500 grams in weight. The Pacific herring is silver, with unspined fins and a deep caudal fin.

The life cycle of herring is unique and includes spawning, feeding, migration, and maturation stages. A critical aspect of the herring life cycle is that once females reach maturity around 3 to 4, they can spawn up to 9 times in their lifetime, with the average female spawning six times. This, of course, depends on whether or not they survive, including surviving the herring sac roe kill fishery.

Many consider the Pacific herring to be the single most important species in our coastal waters because herring convert plankton to energy that powers our entire coastal ecosystem.

Understanding the Herring Spawn

Herring gather in large schools in shallow waters or estuaries during their spawning period, with a single spawning event stretching over many kilometres of shoreline. 18% of British Columbia’s coast has been classified as herring spawning habitat. One interesting fact about Pacific herring is that they exhibit strong spawning site fidelity, meaning they typically return to the same spawning grounds yearly. This behaviour is a common trait among many fish species and is crucial for the survival and maintenance of distinct herring populations. Site fidelity in spawning helps ensure that herring spawn in locations with environmental conditions suitable for the survival of their eggs and larvae. Research has found that the homing behaviour Pacific herring exhibit is driven by a combination of environmental cues, such as water temperature, salinity, and possibly even magnetic fields, as well as learned social behaviours.

Females lay their sticky eggs on seaweed, sea grass, or rocks, which are then fertilized by the milt (sperm) male herring release into the water. The milt turns the water in the spawning ground into a distinctive chalky white, as seen in the images. The eggs’ adhesion is vital for protecting them from being washed away or eaten by predators, although many are consumed by various species. The eggs incubate for about 10 days to a few weeks, depending on the water temperature. During this time, they develop into larvae while still attached to the substrate.

A single mature female herring can spawn 20,000 eggs annually, with the average female herring spawning between 6 to 8 times in her lifetime. This means a female herring has the potential to spawn close to 200,000 eggs in her lifetime. One of the many criticisms of the herring sac roe kill fishery is that it removes reproductive females from herring populations.

After hatching, juvenile herring feed mainly on zooplankton until they reach maturity at two years of age. Mature herring migrate to deeper water, feeding on various organisms such as crustaceans, mollusks, worms and other small fish.

Why are Herring Important for The Great Bear Sea?

Herring are an important keystone species on the Great Bear Coast and are considered the foundation of the coastal food web. Their importance for the coastal food web begins when they are eggs, as their spawning grounds become a weeks-long feast for many marine species and coastal land mammals, including black bears, wolves, sea lions, seals, humpback whales, gray whales, orcas, and birds. They converge on the spawning grounds to feed on herring and their eggs. The herring spawn is so important to the Great Bear Coast ecosystem that surf scoters and gray whales time their northward migrations to feast on it. In the wider Great Bear Sea, herring are an essential part of the diet of many fish. For example, the diets of Chinook Salmon, Coho Salmon, and Lingcod consist of 62%, 58%, and 71% herring, respectively. This means that herring transfer the energy from the plankton they feed on as juveniles to the entire Great Bear Coast ecosystem. Herring literally power the Great Bear Sea.

Why are Herring Important for Communities on The Great Bear Coast?

Herring are the foundation of Great Bear Coast communities, with First Nations’ harvesting of this fish going back at least 10,000 years. In fact, “throughout the Pacific Northwest, herring bones are among the most abundant fish remains found in ancient coastal settlements, indicating that herring were a critical food resource.” One traditional herring harvesting technique First Nations use is the sustainable spawn on kelp. Instead of taking the entire fish, roe on kelp involves harvesting the roe from hemlock branches, seaweed, or kelp. Herring roe is a source of protein, iron, vitamin B1, and riboflavin for coastal First Nations. This sustainable practice stands in contrast to the herring sac roe kill fishery.

The importance of herring for our coast and coastal communities extends beyond the spawn on kelp fishery, as herring are prey for many commercial species, including salmon, halibut, lingcod, sablefish, and rockfish. If herring disappeared from our coast, these species and many more would experience population collapses, which would have a negative economic impact on the coastal communities. It is important to understand that herring exist in an ecosystem that greatly depends on them. Therefore, from a fisheries management perspective, herring need to be managed as part of the larger ecosystem instead of being considered in isolation — an approach that has contributed to the current herring population declines.

Herring Decline

Under the guidance of the DFO, Pacific herring numbers have decreased up to 96% in some areas in the last fifty years. There are several reasons for this decline, but researchers have identified commercial overfishing and DFO mismanagement as the main culprits. The most detrimental type of commercial fishing for herring is the sac roe herring kill fishery, as the entire fish is harvested just for the roe. The remaining 90% of the catch biomass, including the entire male, is processed into dog food, fertilizer, and feed for farmed salmon. Many consider this fishery to be wasteful. As already mentioned, the kill fishery removes reproductive females from herring populations.

The DFO has consistently overestimated herring populations, resulting in overfishing. These overestimations are influenced by several factors, including industry pressure and even ignoring the findings of its own scientists.

One flaw in the DFO approach to herring stock management is that it lacks essential spatial considerations. First Nations have always understood that herring form distinct sub-stocks, each connected to specific spawning areas, resulting in First Nations herring management taking place at the level of individual spawning sites. Because the DFO has used a much larger regional spatial approach and has relied on a maximum sustainable yield single-species approach to fisheries management, four of the five Pacific herring fishing grounds collapsed following the 2015 opening. The 2022 opening of the Strait of Georgia herring fishery was disastrous and illustrates that the DFO once again overestimated herring populations and size while ignoring First Nations on the coast, such as the Heiltsuk, who have consistently advocated for sustainable herring fisheries. However, the DFO has constantly gone against the science and management agreements with First Nations. According to McKechnie et al., the most likely “explanation for the difference between the modern pattern of variability in herring abundance and the long-term archaeological record is the onset of industrial-scale commercial fishing.”

The disastrous 2022 herring fishery has had some impact on herring fisheries management, as both the Haida Gwaii and West Vancouver Island herring fisheries are closed for the 2024 season. However, the Strait of Georgia will be open for Roe (and Food and Bait, Special Use) fisheries at a 10% harvest rate to a maximum of 8,058 tons. Seine boats have been allocated 1,861 tons, and gillnets may harvest 3,159 tons. Many commentators see the opening of the Strait of Georgia herring sac roe kill fishery as problematic due to the historic overfishing of this specific population. In the draft integrated fisheries management plan, DFO presented several harvest possibilities. However, in the end, DFO selected the scenario allowing for increased harvest, boosting the quota in tonnage by 1,433 from 2022/2023. The Prince Rupert district is also open for the sac roe kill fishery in 2024 with a 5% harvest rate to a maximum of 2,271 tons. Seine boats have been allocated 369 tons, and gillnets may harvest 302 tons. The total allowable catch for this district has increased this year by 485 tons.

Protecting Herring

The only way forward to ensure that herring are protected is the establishment of the Great Bear Sea Marine Protected Area (MPA( Network. The Great Bear Sea Marine Protected Area (MPA) Network will cover about 30% of the sea’s area and consist of existing protected areas and new MPAs. Establishing MPAs at critical spawning areas will allow herring populations to recover. When keystone species like herring thrive, so will other marine animals and, by extension, the entire marine ecosystem. A healthy marine ecosystem is critical not only for future biodiversity but also for the sustainability of coastal economies.