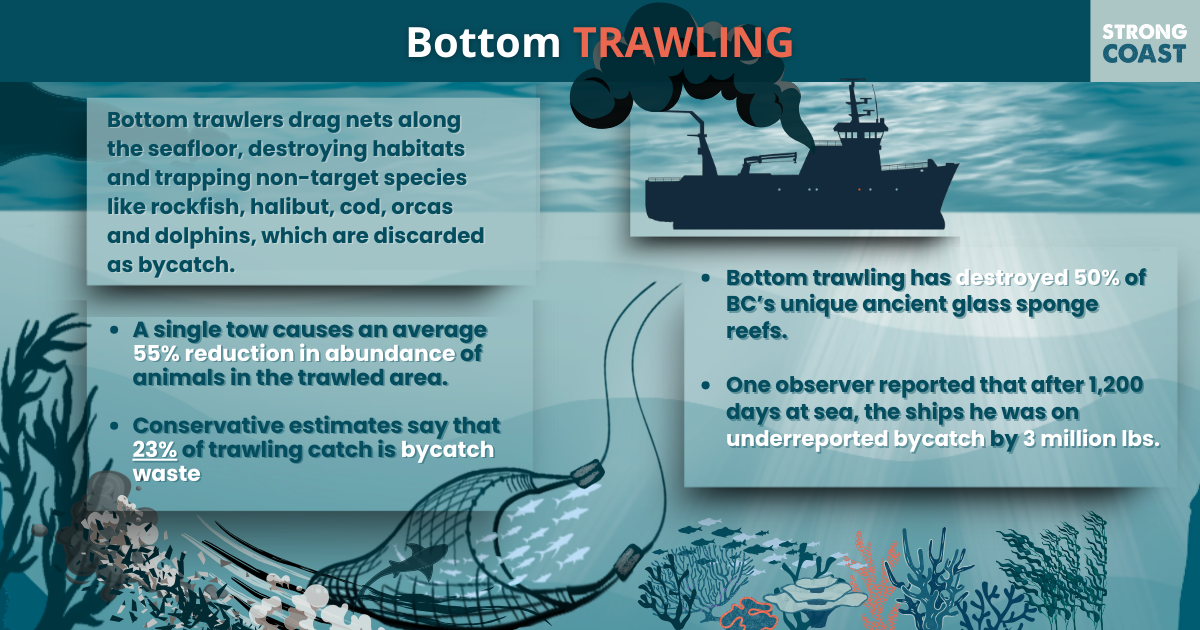

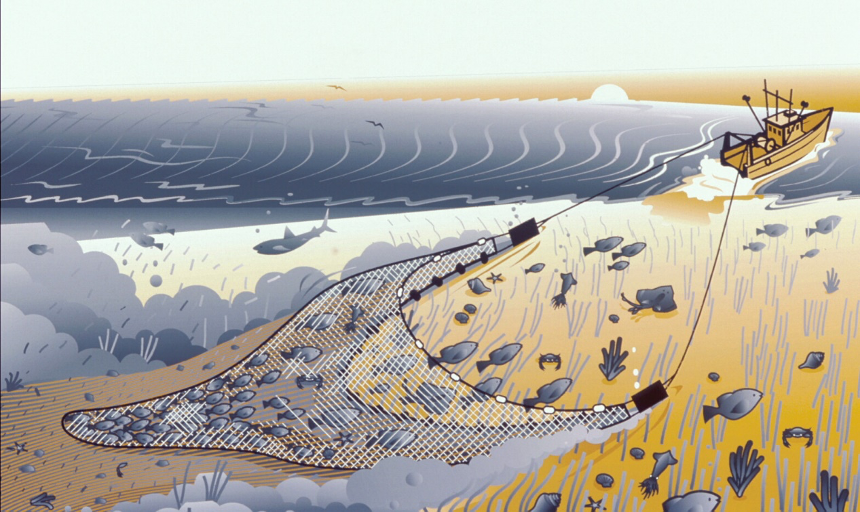

Bottom trawling, which involves dragging weighted nets along the seafloor to capture groundfish and other marine life, has been used on the BC Coast for many years. Trawling allows for the capture of large quantities of fish in a relatively short time but has negative impacts, including damaging delicate habitats, disrupting ecosystems by overfishing groundfish, reducing biodiversity, and unacceptably high bycatch. Bycatch refers to non-target species scooped up during the bottom trawl process. The mortality rate of bycatch depends on the marine species, but bycatch is widely recognized as wasteful and a significant problem in the trawling industry.

In British Columbia, the average annual bottom trawling catch is 38,500 tonnes, including groundfish and shrimp. This is unsustainable and puts immense pressure on marine ecosystems. In the end, bottom trawling contributes to the decline of important commercial species.

Bottom Trawling in BC

Currently, 144 groundfish trawl licenses operate in BC. The majority of these licenses are Option A, which allows for both bottom and mid-water trawl, with the remainder being Option B licenses, which allow for bottom trawling only. Boats with Option A licenses can bottom trawl in the following areas:

Area 4 Chatham Sound, Porcher Island

Area 5 Grenville Channel, Principe Channel

Area 6 Princess Royal Island

Area 7 Price Island, Hunter Island

Area 8 Fitz Hugh Sound

Area 9 Calvert Island, Rivers Inlet

Area 10 Cranstown Point, Table Island

Area 11 Cape Caution, Westcott Point

Area 21/22 Tzuquanah Point, Nitinat Lake

Area 23 Cape Beale, Ucluelet

Area 24 Cox Point, Estevan Point

Area 25 Nootka Sound, Esperanza Inlet

Area 26 Union Island, Solander Island

Area 27 Solander Island, Lawn Point, Cape Scott

Boats with Option B licenses can bottom trawl in the following areas:

Area 12: Northern Johnstone Strait, including Port Hardy and Robson Bight.

Area 13: Quadra Island and Cortes Island.

Area 14: From Oyster River to Parksville.

Area 15: Brettell Point to Powell River.

Area 16: Texada Island, Lasqueti Island, and Jervis Inlet.

Area 17: Nanoose Bay to Galiano Island.

Area 18: Mayne Island and Saanich Peninsula.

Area 19: Saanich Peninsula to William Head.

Area 20: Sooke to Bonilla Point Lighthouse.

Area 29: Lower Georgia Strait, which includes the Fraser River and parts of the Sunshine Coast near Chapman Creek and Davis Bay.

Areas 12 to 20 and 29 are reserved for Option B trawl licenses and represent the only areas that Option B licenses are allowed to bottom trawl. Option A trawl licenses can also mid-water trawl coast-wide. Option A licensed boats have fewer restrictions in terms of the number of trips and landings per month than Option B licensed boats.

The Damage Caused by Bottom Trawling

While not as bad as in other regions of the world, the bottom trawling situation in BC is far from perfect. Historically, bottom trawling has caused significant damage to important ocean habitats and BC’s marine ecosystem. For instance, dragging the ocean floor has destroyed 50% of BC’s unique ancient glass sponge reefs, contributing to the release of more than one billion tonnes of carbon dioxide caused by bottom trawling globally. Some regulatory action has been taken, including the creation of closed zones on the BC coast to protect ancient glass sponge reefs.

However, the groundfish trawl, which includes both bottom and mid-water trawling, is still a problem in BC waters. Conservative estimates say that 23% of trawling catch is bycatch waste, which is thrown back into the ocean. Some bycatch are protected species, such as yelloweye and bocaccio rockfish. With the average annual trawl catch estimated at 38,500 tonnes in BC, this means that in BC, 8,855 tonnes of fish and other marine species are thrown back into the ocean, either dead or with little chance of survival. The mortality rate of bycatch depends on the species. For instance, while the mortality rate of halibut bycatch is around 15%, the mortality rate of rockfish is close to 100% due to swimbladder expansion. However, even at 15%, the bottom trawl bycatch mortality of halibut amounts to 290,000 pounds.

However, an investigative piece by The Narwhal on the BC trawl industry found that a significant amount of bycatch goes unreported. This is because once a ship reaches its bycatch limit, it has to shut down for the season. The result of this, according to The Narwhal, is fishery observers facing intimidation by ship captains and crew to underreport. In its investigation, The Narwhal interviewed one observer, who estimated that in his 1,200 or so days at sea as an observer, the ships he was on underreported bycatch by 3 million pounds. This suggests that bycatch waste in BC is much higher than officially reported.

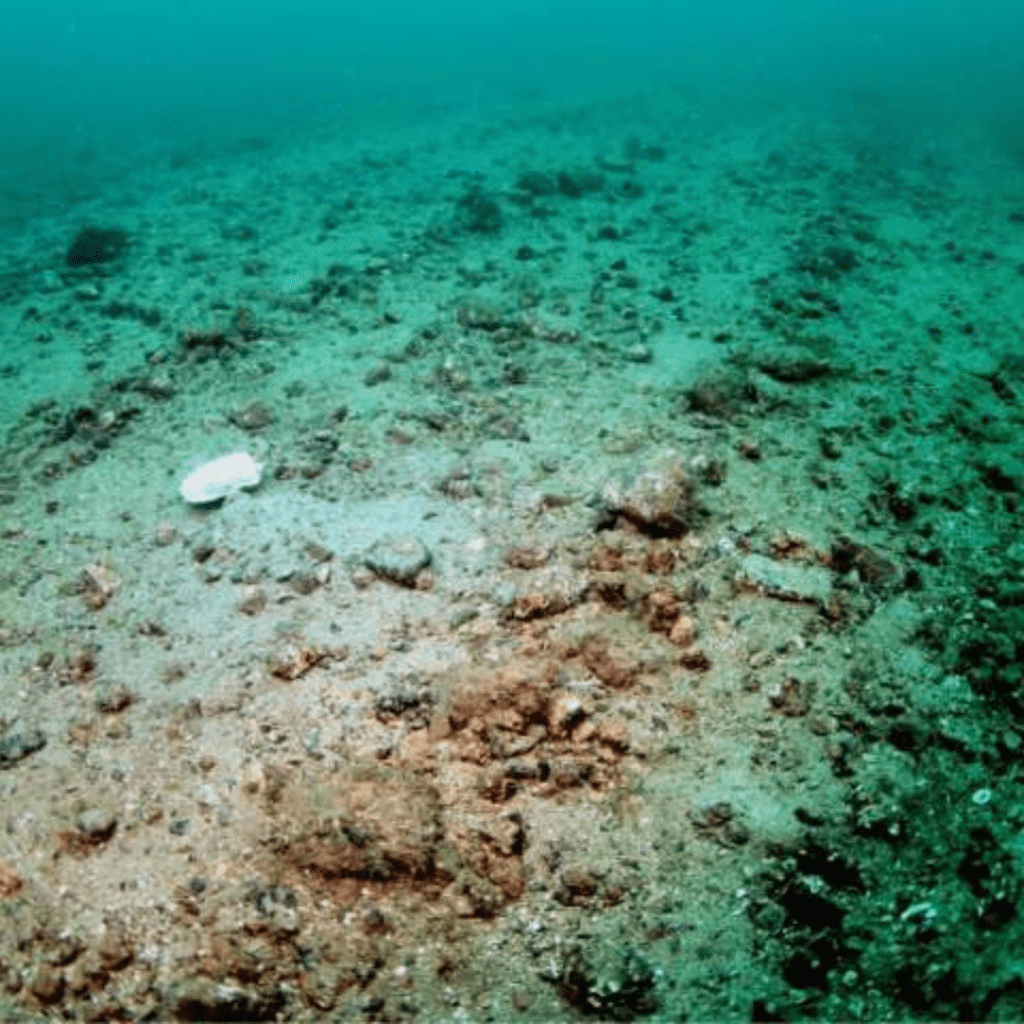

A report by Fauna & Flora International highlighted that at least 1.1 million square kilometres of seabed globally are exposed to at least one pass of a trawl every year. Delicate habitats (such as the cold-water coral reefs we have in BC) are more vulnerable to negative impacts from dragging than other kinds of habitats like sandy plains. When damaged, reefs recover exceptionally slowly or not at all, with effects lasting well over 100 years.

Neighbouring Alaska recently experienced the impact that bottom trawl activities can have on crabs. In 2022, the sudden cancellation of the snow crab harvest in Alaska’s coastal waters caused an estimated US$290 million in economic damages and triggered calls for the issuance of an emergency declaration. The 2023-24 season was also cancelled. Some of the target species of the Alaskan bottom trawl include various types of rockfish, flounder, sole, and Pacific cod.

While acknowledging other factors like climate change, Alaskan crabbers also blame dragging companies for destroying underwater habitats, negatively impacting crab populations.

The issue is not just that specific species will collapse. If even one species in our waters experiences drastic population declines, it could adversely affect the entire marine ecosystem. This will result in a marine desert, and local economies that rely on marine resources will suffer greatly. However, these realities seem to be of little concern for the trawling industry, which is currently in the middle of a PR campaign that vastly underplays bycatch and the harm that bottom trawling does to marine ecosystems.

History of Bottom Trawling in the United Kingdom: What British Columbia Should Not Do

Bottom trawling in the United Kingdom has been an unmitigated disaster. A study found that bottom trawling has taken place in 98% of the United Kingdom marine protected areas (MPAs), with many protected areas showing complete surface area trawling. Dr. Jean-Luc Solandt, principal specialist in MPAs at the Marine Conservation Society in the UK, says the research demonstrates that MPAs in the UK are failing to safeguard marine habitats. Nick Underdown, head of campaigns at Open Seas, argues that the Scottish government’s claim that MPAs are protecting 30% of Scottish oceans is bluewashing.

“While bottom-trawling is still allowed, we will continue to release more carbon from the seafloor and prevent complex carbon-storing habitats from recovering.”

Dr Jean-Luc Solandt, principal specialist in marine protected areas at the Marine Conservation Society

In the UK, until very recently, many of the MPAs were “paper parks,” which researcher Michael Slezak defined as established MPAs on paper that, in reality, lack sufficient management and enforcement to achieve their conservation goals effectively. According to Slezak’s research in 2014, only 24% of the world’s MPAs had sound management.

“Paper designations are worse than useless, because they give the illusion of protection when the health of Scotland’s seas is deteriorating.”

Nick Underdown, head of campaigns at Open Seas

However, the situation is improving in the UK, as in March 2024, the UK banned bottom trawling in 13 of its marine protected areas, covering a total of 4,000 sq km. This important move has sparked protest from the French government and the French bottom trawl industry. The French government is being accused of hypocrisy as France, Costa Rica, and the UK launched the High Ambition Coalition for Nature & People in 2022 with the explicit purpose of protecting 30% of land and sea by 2030. France’s protest places the country as a barrier to achieving ocean sustainability even though France claims to support the 30×30 initiative, which is a global agreement to protect 30% of the earth’s waters and land by 2030.

How Can We Control or Reverse the Impacts of Dragging?

Enhanced protection from bottom trawling on the BC coast will only come with establishing the Great Bear Sea Marine Protected Area (MPA) Network. The UK example indicates that the Great Bear Sea MPA Network needs to be committed to robust protection measures and enforcement, which comes from solid management. While government involvement is going to be important, it is equally critical to engage coastal communities. With their on-the-ground (or rather, on-the-water) expertise and vested interest in maintaining the longevity of coastal resources, they will play a significant role in ensuring that the goals of the MPA network are met. Ultimately, the success of this MPA network will be measured not just in terms of its protection of marine resources, but also in its ability to uplift coastal economies through the creation of sustainable fisheries.